The Legislative History of NEA and NEH

March 22, 2017

Art like life should be free, since both are experimental.

~George Santayana

by Emily Lanza

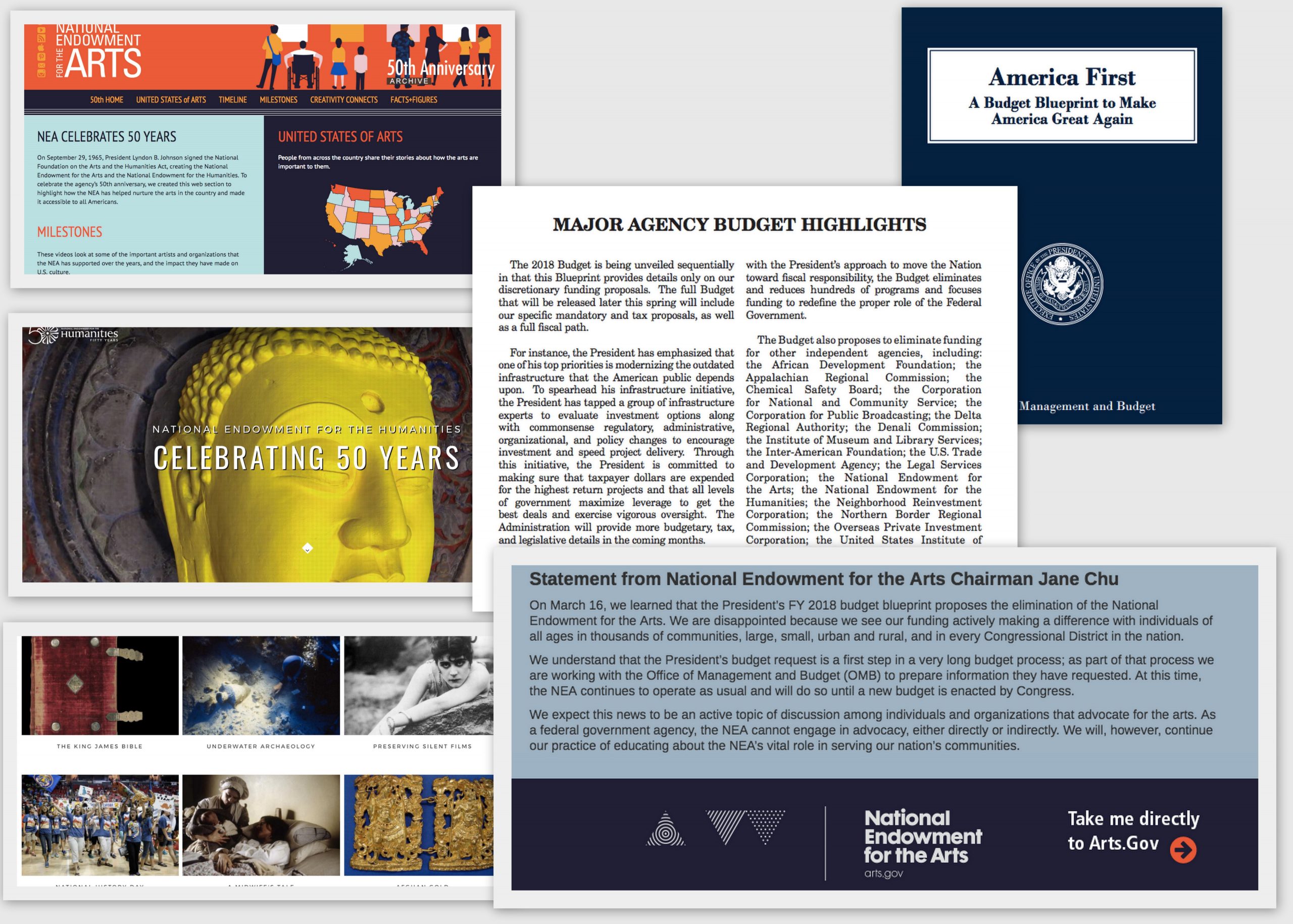

On March 16, 2017, the President of the United States announced his proposed budget for 2018, which outlines his plans to eliminate the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) and the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH). Notwithstanding the political arguments surrounding this issue or the likelihood of manifestation of these plans, in order to fully grasp their intended role and current impact on the arts and humanities communities, it is important to consider why Congress created these agencies in the first place, over fifty years ago.

On March 16, 2017, the President of the United States announced his proposed budget for 2018, which outlines his plans to eliminate the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) and the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH). Notwithstanding the political arguments surrounding this issue or the likelihood of manifestation of these plans, in order to fully grasp their intended role and current impact on the arts and humanities communities, it is important to consider why Congress created these agencies in the first place, over fifty years ago.

Legislative history not only reveals the past but also informs the present, specifically the basic role of an agency or program. Thus, in order to create a more comprehensive and convincing argument in favor of these agencies having a future, we must first turn to the past. This article considers the significance of the two agencies from a legislative history perspective and examines how the legislative history can affect the future of these programs.

Overview of NEA and NEH

The United States is one of few nations not to have a Ministry or Department of Culture. Instead, some of the duties a Ministry of Culture would undertake are designated to the NEA and NEH. Both agencies are part of the National Foundation on the Arts and the Humanities (“National Foundation”). The National Foundation was established by the National Foundation on the Arts and the Humanities Act of 1965 (“Act”) to promote a broadly conceived policy of support for the arts and humanities throughout the United States. The NEA provides financial grants to individuals, nonprofit groups, and the States to support engagement in the creative and performing arts while the NEH provides grants to support academic and scholarly humanistic teaching, learning, and research.

As independent agencies, the NEA and NEH each have a chairman and an advisory council. Appointed by the President with the advice and consent of the Senate, the chairman of NEH and the chairman of NEA are leaders in his/her particular field. William Drea Adams, an educator and the current NEH chairman, had previously served as President of Bucknell University and Colby College. With a background in arts administration, Jane Chu currently serves as the chairman of the NEA and is also herself an accomplished artist and musician.

While congressional appropriations are the primary source of funding for both agencies, the NEA and NEH can accept tax deductible donations including gifts of stock and other property. However, under government ethics restrictions, these agencies may accept donations from an organization that is eligible for an endowment grant “only if that organization confirms in writing that it has not received a grant in the past three years and does not intend to apply for a grant for the next three years.”

Legislative History of the National Foundation on the Arts and the Humanities Act of 1965

Bills proposing the National Foundation were introduced in the House of Representatives and the Senate on March 10, 1965. The Special Subcommittee on Arts and Humanities of the Senate Committee on the Labor and Public Welfare and the Special Subcommittee on Labor of the House Committee on Education and Labor held hearings on the proposed Foundation during February and March of 1965. By September of 1965, an amended Senate Bill (S.1483) passed both houses, and President Lyndon Johnson signed the National Foundation on the Arts and the Humanities Act of 1965 into law.

Congress heard over fifty witnesses during seven days of hearings to discuss the proposed National Foundation on the Arts and Humanities, providing a robust legislative history. Three themes arise from the legislative history of this Act and the foundation of NEA and NEH: (1) the need to support the arts and humanities financially; (2) such support is in the national interest; and (3) that the federal government should accept the role and responsibility of providing this support.

The Need for Financial Support of the Arts and Humanities

According to the legislative history for establishing the National Foundation, Members of Congress and the relevant stakeholders at the time naturally focused on the financial needs of the arts and humanities, as the fundamental purpose of these agencies is to provide grants. However, Congress did not intend the National Foundation to serve as the only or primary supporter of arts and humanities in the United States, instead it was to act as a catalyst that “stimulate[s] private philanthropy for cultural endeavors and State activities to benefit the arts.” Congress noted that private financial support in the arts and humanities was “lagging,” as the number of endowment and foundation gifts to arts and cultural institutions was dropping. In order to encourage such donations, Congress authorized the proposed agencies to match funds donated from private sources, for Congress believed that financial support originating from multiple sources best reflected the operations of a democratic society.

Similarly, through the agencies’ state grant programs, Congress intended to increase the opportunities for access to the arts and humanities for everyone across the country. Congress hoped that encouraging and supporting the arts and humanities at the local level would allow a greater number of citizens to enjoy and appreciate the arts beyond those that live in the nation’s cultural centers. Thus, this collaborative approach between the federal and state governments towards funding the arts and humanities represented a recurring theme in the legislative history, ultimately shaping the structure and activities of the agencies.

National Interest in Supporting the Arts and Humanities

The importance of the arts and humanities to the nation was another predominant theme during the legislative history of the National Foundation on the Arts and the Humanities Act of 1965 and the creation of NEA and NEH. Together Members of Congress and stakeholders at the Hearings discussed the role of the arts and humanities in developing a successful democratic society. More specifically, many people explained that the arts and humanities teach us to think, to express ourselves, and to solve problems – all valuable and necessary qualities of productive citizens of a democratic society. Barnaby C. Keeney, President of Brown University and the Chairman of the Commission on the Humanities, eloquently stated:

“Only through the best ideas and the best teaching can we cope with the problems that surround us and the opportunities that lie beyond these problems. Our fulfillment as a Nation depends on the development of our minds; and our relations to one another depend upon our understanding of one another and of our society. The humanities and arts, therefore, are at the center of our lives and are of prime importance to the Nation and to ourselves. Very simply stated, it is in the national interest that the humanities and arts develop exceedingly well.”

Related to the civic benefits of the arts and humanities, Members of Congress and stakeholders also discussed the role of arts and humanities in education and employment – two issue areas of particular relevance to many throughout the country. Several witnesses, including the Commissioner of Education, mentioned the role of arts and humanities as a necessary component of a well-rounded education program from grade school to university. Similarly, others considered how the arts and humanities provide opportunities for employment and encourage people to realize their potential in their chosen fields by allowing them to acquire and develop certain skills – namely the skills involving expression and critical thinking.

Lastly, Members of Congress emphasized that the arts and humanities benefit the whole nation by assisting with our understanding of other peoples and cultures and by maintaining a positive image of the United States throughout the world. According to Senator Kennedy, arts and humanities “provide a vehicle for understanding and respect between men of all races and cultures.” Both the Senate Report associated with the Act and the Hearings explained that dedicated federal agencies to the arts and humanities “would serve not only to deepen our understanding of our friends and allies throughout the world, but would strengthen the projection of our Nation’s cultural life abroad, and enable us better to overcome the increasing ‘cultural offensive’ being waged by Communist ideologies.” Congress noted that the arts and humanities act as important cultural ambassadors both at home and abroad.

Federal Government Role in the Arts and Humanities

While legislative history reveals that Congress generally agreed about the importance and the need for financial support of the arts and humanities, perhaps the most critical issue discussed during the Hearings was the federal government’s role and responsibility in these areas. Those involved in the legislative history of the Act believed that the federal government’s interest and leadership in the arts and humanities would serve as the most effective manifestation of the national importance of these fields. Several remarked that the federal government’s involvement in the arts and humanities would “set[] a national tone of interest” and thus generate more visibility for the arts and humanities at the national level. Similarly, other stakeholders at the Hearings noted that the federal government is the best entity to foster cooperation between organizations and other government agencies by offering coordination and direction at the federal level.

Moreover, the legislative history demonstrates that many Members of Congress were keenly aware of the federal government’s involvement in another academic field: science. In the 1960s at the height of the space race, the U.S. government placed significant emphasis on science and technological development, which was viewed at that time as a priority for national security. One witness remarked during the first day of the hearings that a “substantial proportion of our attention and our national budget is directed toward motion in space. Our aspirations and goals are linked, literally, with the moon and the stars.” Congress intended with the National Foundation on the Arts and the Humanities Act to correct the imbalance between federal support for science and federal support for the arts and humanities.

Using the Past to Guide the Present & Future

So what does the legislative history of the National Foundation on the Arts and the Humanities Act of 1965 tell us about the present and future of the NEA and NEH? One of the points of delving into an Act’s legislative history is to understand congressional intent. In the case of the National Foundation on the Arts and the Humanities Act, Congress intended to bestow on the federal government the responsibility to support, both financially and administratively, the arts and humanities. In order to justify this responsibility, Congress repeatedly referred to the basic fundamentals of our society and nation that are as relevant today as fifty years ago and, consequently, will likely be as relevant fifty years from now.

These fundamental principles include democracy, productivity, and leadership. In 1965, Congress understood that these principles, which are entwined with the arts and humanities, make up the foundation of our society and country. Congress favored a democratic approach towards funding the arts and humanities in which the federal government collaborates with private donors to fund projects that would enable a greater number of people across the country to enjoy and benefit from the arts and humanities. Congress also highlighted that the arts and humanities foster the productivity of the nation’s citizens, by providing opportunities to develop critical skills necessary for success in the context of education and employment. Likewise, the arts and humanities are important vehicles to demonstrate American influence and leadership at home and abroad.

While the specific concern about the threat of “Communist ideologies” may be indicative of the 1960s, the service that arts and humanities can provide to the nation as a whole is still relevant today. Such relevance stems from the universal and democratic principles that shape our identity as a nation and society, which Congress discussed and debated while creating the NEA and NEH during the legislative history of the National Foundation on the Arts and the Humanities Act of 1965.

In 2016, Congress appropriated $148 million (0.003 percent of the budget) to the NEA and the same amount to NEH. Considering the $3.9 trillion budget of the federal government, the NEA and NEH offer bargain services to provide the basic fundamentals of an enlightened citizenry, democracy, productivity, and leadership. Cutting these agencies, while only a small part of the federal budget, would have a disproportionate impact on the prosperity of the nation. The nation cannot afford to ignore the lessons and insight revealed by the legislative history of these two agencies formed only fifty years ago.

Select Sources:

- Executive Off. of the President of the U.S.: Office of Mgmt.& Budget, America First: A Budget Blueprint to Make America Great Again,5 (2017), available at https://tinyurl.com/k9aj588.

- Pub.L.No.89-209,79 Stat.845 (1965). Preamble to the Act “To provide for the establishment of the National Foundation on the Arts and the Humanities to promote progress and scholarship in the humanities and the arts in the United States.” Pub.L.No.89-209,79 Stat.845 (1965).

- 20 U.S.C.§ 954(b),(c),(f).

- 20 U.S.C.§ 956 (a), (b),(c),(f).

- See, e.g.,NEA,2015 ANNUAL REPORT 14 (2016), available at https://www.arts.gov/sites/default/files/2015%20Annual%20Report.pdf.

- 20 U.S.C.§ 959(a)(2).“Other property” can include works of art.

NEA, ABOUT THE NEA: DONATE, available at https://www.arts.gov/about/donate.

H.R.6050,89th Cong.(1st Sess.1965) (introduced by Rep.Thompson,D-

NJ). - S.1483,89th Cong.(1st Sess.1965)(introduced by Sens. Pell D-RI, Javitas R-NY, Gruening D-AK). Hearings were held on February 23-26 and March 3-5,1965.

President Lyndon Johnson remarked at the signing of the bill that “What this bill really does is to bring active support to this great national asset, to make fresher the winds of art in this great land of ours.The arts and the humanities belong to the people, for it is, after all, the people who create them.” The American Presidency Project,“Remarks at the Signing of the Arts and Humanities Bill,” http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=27279. - S.REP.NO.89-300 (1965). National Arts and Humanities Foundations: Joint Hearing Before the Special Subcomm. on Arts and Humanities of the S.Comm.on Labor and Pub.Welfare and the Special Subcomm. on Labor of the H.Comm.on Education and Labor,89th Cong.5,54 (1965)(hereinafter “Hearing”) (statements of/by Sen.Jacob K.Javits, Sen.Edward M.Kennedy, Rep.John E.Fogarty, Dr. Barnaby Keeney, Pres., Brown University; and Chairman,Commission on the Humanities, Roger L.Stevens, Chairman, John F.Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts; testimony and statement of Francis Keppel, Commissioner of Education; John A.Ryan,President,Philadelphia Federation of Teachers, and American Federation of Teachers,AFL-CIO; Rep.John E.Fogarty; Rockefeller Panel Report on the Future of Theater,Dance,Music in America; statement of Alvin C. Eurich, Pres., Aspen Institute for Humanistic Studies; remarks of Sen.Pell; statement of Francis Keppel, Commissioner of Education).

- Philip Bump,”Trump reportedly wants to cut cultural programs that make up 0.02 percent of federal spending,” Wash.Post. (Jan.19,2017), available at https://tinyurl.com/lsl5rjm.

*About the Author: Emily Lanza is currently Counsel for Policy and International Affairs at the U.S. Copyright Office. She received her J.D. in 2013 from the Georgetown University Law Center. Prior to law school, she studied archaeology and worked for museums in various capacities. She can be reached at emilyla8@gmail.com.

From the Author: While many of the readers of this article are already aware of the importance of arts and humanities funding, this article, instead intends to select concepts from the legislative history that may be used to inform future discussions.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed here are solely of the author and do not express the views and opinions of the U.S. Copyright Office.

Disclaimer: This article is for educational purposes only and is not meant to provide legal advice. Readers should not construe or rely on any comment or statement in this article as legal advice. For legal advice, readers should seek an attorney.

You must be logged in to post a comment.