Remembering Modigliani: Italy’s Ongoing Battle against Forgery

July 17, 2020

By Tatyana Kalaydjian Serraino.

The year 2020 marks the anniversary of Amedeo Modigliani’s death. The Italian-Jewish modernist painter passed away in Paris in January 1920 at the age of 35. He died destitute, his internationally-renowned artistic oeuvre remained officially undocumented and in demand, creating an irresistibly tantalizing circumstance for art forgers.[1] Two days after his death, his grief-stricken wife committed suicide, leaving behind a single soul to benefit from Modigliani’s works: his 18-month-old daughter. Modigliani’s legacy is marred by countless.[2] Today, he is one of the most frequently forged artists of all time with more than one thousand imitations populating the world.[3]

This year, exhibitions were scheduled to take place in his native city of Livorno and in Vienna. Similarly, the Amedeo Modigliani Institute in Rome is planning an ambitious showcase of all 337 of Modigliani’s artworks for a centennial commemoration of his death.[4]

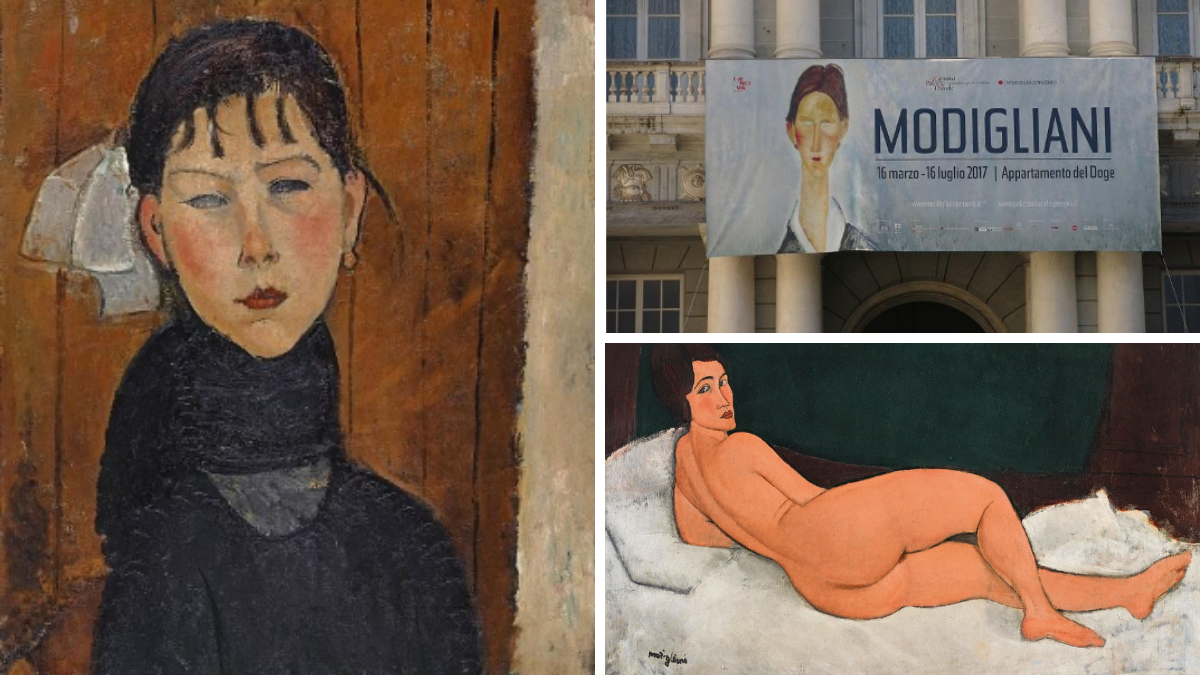

A Massive Collection of Forgeries

Modigliani’s works feature soulful portraits characterized by slender necks, sinuous bodies, and oval faces. His unique and easily replicable style, coupled with his paintings’ exorbitant prices, has tempted forgers from far and wide (Russia, Serbia and Italy).[5] In 2018, Modigliani’s painting “Nu couché” (1917) sold for $157.2 million, setting new records for the most expensive work to ever be sold at a Sotheby’s auction.[6]

Amedeo Modigliani, “Nu Couché (Sur Le Coté Gauche)” (1917), sold at Sotheby’s New York at the Impressionist & Modern Art Evening Sale in May 2018 for $152.2 million. Source: Sotheby’s.

Perhaps the most notorious Modigliani forgery came to light in 2017 when thousands of visitors descended upon Genoa’s Ducal Palace (Palazzo Ducale) to admire 21 Modigliani paintings thought to be worth millions of euros.[7] All of these were later declared to be fakes.[8] The legal repercussions of the fiasco are still felt today, with the Italian police in the dark amidst unanswered questions regarding the event and the efficacy of Italian law in bringing perpetrators of such an art crime to justice.

Tuscan art critic, collector and notable Modigliani expert Carlo Pepi first raised the alarm when he relayed his concerns about the paintings’ authenticity to an art fraud unit.[9] He later claimed the paintings were “missing that three dimensional elegance of Modigliani…”[10] The show was shut down three days early on July 13th, 2017, and its contents handed over to the authorities for investigation. After careful examination, experts confirmed that 20 of the 21 paintings seized by the prosecutors were forgeries. In line with Article 169 of the Italian Copyright Act,[11] the Modigliani fakes from the Genoa debacle now face possible destruction.[12]

Amedeo Modigliani, “Marie Daughter of the People” (1918). The Painting was declared to be a fake by expert Carlo Pepi. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Shortly after the exhibition’s closing, the authorities identified three suspects to prosecute: Massimo Vita Zelman, the president of MondoMostre Skira, the company that organized the show; Rudy Chiappini, the show’s curator; and Joseph Guttmann, an art dealer who loaned some of the exhibited works.[13] Two years later, on March 13th, 2019, Italian police named a further three suspects: Piero Pedrazzini, the owner of one of the exhibited works; Nicolò Sponzilli, a MondoMostre Skira director; and Rosa Fasan, a MondoMostre Skira employee.[14] Having identified likely suspects, Italian prosecutors were left with the task of determining if there was enough evidence to press charges for receiving and circulating the fake paintings.[15] So far, they have filed accusations of counterfeiting and fraud.[16]

Understanding Forgery as a Philosophical, Moral, and Legal Offense

Before shedding light on how art forgery is prosecuted and punished under Italian law, let’s examine what exactly constitutes an act of art forgery. The notion of forgery as a condemnable act is only applicable when seen against the norms of Western consumerist society, in which art is a commodity whose market value is determined by aesthetic and non-aesthetic factors such as the name of the artist.

A good forgery requires skill; in re-creating works of art so precisely, forgers can be considered artists themselves.[17] Indeed, the portraits of the infamous forger Elmyr de Hory, who made countless forgeries of many artists including Matisse and Modigliani, were exhibited to a visiting public from February to April this year, thus celebrating him as an creator, as opposed to condemning him as a forger.[18]

As author Alfred Lessing argues, original artworks, even if aesthetically identical to their forged equivalents,[19] are always superior because they possess “artistic integrity.”[20] Authentic works reflect not only the genuine creativity of their creators, but also the particular historical and cultural context in which they were produced.[21] Forgeries are deemed less valuable than originals because they lack the very hallmark of western art’s value: its creativity, and by extension, its ability to further our view and understanding of the world.[22]

Furthermore, forgeries involve intentional deception, making them “morally offensive.”[23] It is particularly embarrassing for art critics and institutions to realize they were made to believe that something inferior is superior (here defined in terms of financial value and artistic prestige).[24] To return to the case of the Modigliani exhibition, a spokesperson from the Palazzo Ducale claimed that the Palazzo was the “injured party” and would not hesitate to take legal action.[25] They further clarified that they had “outsourced the organization of the show” as well as the selection of exhibited works, and they would seek “legal protection for [their] rights and public image.”[26]

The Ducal Palace in Genoa, Italy, featuring an exhibition poster of the 2017 Modigliani exhibit. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Italian Law on Forgeries

The legal problem of forgeries originates from the blatant fact that they “cheat their purchasers of money.”[27] As such, the Modigliani forgeries prompted a class action lawsuit to reimburse visitors for their exhibition tickets and travel expenses.[28]

Under Italian law, an accusation of art forgery can result in legal action in both civil and criminal courts.[29] The Italian Copyright Act (Law 633/1941) outlines that claiming authorship of an artwork is within the jurisdiction of civil courts.[30] This is precisely what occurred to the Italian opera singer Giuseppe Zecchillo; he was accused by the Piero Manzoni Foundation for attributing 39 alleged forgeries in his possession to the painter Piero Manzoni.[31] Zacchillo was taken to civil court in 2006, on the grounds of the inauthenticity of the paintings; and then subsequently to criminal court in 2009, on the charge of having played a significant role in the creation of the forgeries.[32] In the Modigliani case at hand, however, the forger of the Modigliani works has not yet been identified, so this law does not apply. However, Article 178 of the Italian Cultural Heritage and Landscape Code (Legislative Decree 42/2004) holds accountable not only those who forge artworks, but also those who exhibit works they know to be forgeries; both culprits can be taken to criminal court.[33] Article 178 states that those who circulate forged works of art as authentic with the aim of gaining profit, regardless of whether they participated in the counterfeiting of the works, are punishable in the same way as those who have created forgeries. This usually entails imprisonment of three months to four years and a fine ranging from 103 to 3,099 euros.[34]

Nonetheless, in order to succeed on a criminal charge under this law, irrefutable proof of intent to deceive and financial gain is necessary. The challenge of that standard of evidence, as the American attorney Peter Barry Skolnik states, is that “if a seller represents what he believes, he is guilty of no fraud.”[35] Therefore, without infallible proof, it is easy for the culprits to claim they believed the works to be authentic.

In the Modigliani case, the art dealer Guttmann expressed his belief of the paintings’ authenticity, as confirmed by their “previous certifications, scientific analysis and inclusion in important exhibitions and publications.”[36] The show’s curator Chiappini similarly defended himself, claiming that he had gathered the “information and the documentation” supplied to him for every canvas, and that “if there have been irregularities, you need to go back … to whoever made the first attribution” of authenticity.[37]

It remains questionable whether the defendants’ statements concerning the paintings’ authenticity could be seen as insufficient in the eyes of the court. The court-appointed art expert Isabella Quattrochi, who examined the Modigliani paintings, claimed that the pigment used in all of the suspect paintings was inconsistent with paints Modigliani used.[38] She also pointed out that the paintings’ frames, allegedly contemporaneous to the paintings, had “nothing to do, either in context or in historical period, with Modigliani.”[39]

Nevertheless, “scientific analysis is not foolproof” and “appraisals of experts are just expressions of opinions which … judges may not find convincing.”[40] In previous art fraud cases around the world, some court-appointed experts have been mistaken.[41] Indeed, any statement regarding value or authorship “can be construed as merely opinion.”[42] To conclusively demonstrate intent in a forgery charge, a connection between the fake “and the faker” must be proved, which can often be costly and difficult, as the “chain of title … can be difficult to trace.”[43]

What Can Be Done to Prevent Forgeries

Today, efforts are still being made to combat the countless Modigliani forgeries circulating the world. The Modigliani Project, for example, is a non-profit organization in midtown Manhattan dedicated to researching the work of Modigliani and creating a complete catalogue of his works. Nevertheless, the Project’s director Kenneth Wayne has stated that their mission has proven to be “impossible” due to the countless forgeries created over the years.[44] Other Modigliani experts have also taken on the daunting task. French art historian and esteemed Modigliani expert Marc Restellini has been working on compiling a catalogue raisonné of the artist’s work due to be published in 2021 which will argue that several of formerly disputed paintings are indeed authentic.[45] However, Restellini’s work is reportedly threatened by the Wildenstein Plattner Institute in France, an organization that aims to “reinvent archival research for the digital generation” by putting it online for free.[46] On June 9th, 2020, Restellini and his attorney Dan Levy filed a federal lawsuit in New York against the Wildenstein Plattner Institute to protect the rights to his work and research, arguing that proving that a Modigliani painting is authentic is worth tens of millions of dollars.[47]

The Need for a New Look at Forgeries

Ultimately, while Italian law seems, in principle, rather unforgiving when it comes to the act of art forgery, it lacks a clear implementation pattern when it comes to arguing that someone (apart from the forgers themselves) is aware of the non-authenticity of the artifact. Provided there are no documents that prove otherwise, an authenticity designation is considered just a purely personal opinion.

One thing for certain is that forgery “makes us think … about originality and comparative value.”[48] One may well argue that those who visited the Ducal Palace exhibition were still able to appreciate Modigliani’s, albeit channeled by impersonators. If there were no historical or financial value attached to Modigliani’s paintings, the Genoa fiasco might not have been cast under such a negative light. More broadly, it is undeniable that art forgeries raise questions about the very nature of our perception of art, the construct of art history as a discipline, the ‘greatness’ attached to art by certain artists, and the elite nature of connoisseurship.

Endnotes:

- Francesco Mannoni, Amedeo Modigliani, La Caccia Ai Falsi Non È Ancora Terminata, Giornale di Brescia (Jan. 12, 2020), available at http://www.chiarelettere.it/rassegnastampa/16.%20Giornale%20di%20Brescia_12.01.20.pdf, 34. ↑

- Milton Esterow, The Art Market’s Modigliani Forgery Epidemic, Vanity Fair (May 3, 2017), available at https://www.vanityfair.com/style/2017/05/worlds-most-faked-artists-amedeo-modigliani-picasso. ↑

- Nick Squires, Modigliani paintings once thought to be worth tens of millions now denounced as fakes, The Telegraph (Jan. 10, 2018), available at https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2018/01/10/modigliani-paintings-thought-worth-tens-millions-denounced-fakes/. ↑

- Editorial Board, Modigliani: Give Light to Art, Indiegogo (2020), available at, https://www.indiegogo.com/projects/modigliani-give-light-to-art#/. ↑

- Esterow, supra note 2. ↑

- Isaac Kaplan, $157 Million Modigliani Breaks Sotheby’s Record at Otherwise Underwhelming Impressionist and Modern Sale, Artsy (May 15, 2018), available at https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-157-million-modigliani-breaks-sothebys-record-underwhelming-impressionist-modern-sale. ↑

- Caroline Mortimer, Modigliani art exhibited at Ducal Palace in Genoa revealed to be almost entirely fake, Independent (Jan. 12, 2018), available at https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/art/news/italy-modigliani-fake-show-police-investigation-art-genoa-a8154701.html. ↑

- Katherine McGrath, 20 Works in Major Modigliani Exhibition Have Just Been Confirmed as Forgeries, Architectural Digest (Jan. 11, 2018), available at https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/a-major-modigliani-forgery-scandal-hits-italy. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Sarah Cascone, Visitors to Major Modigliani Exhibition Demand a Refund After an Expert Concludes the Majority of Works Were Fake, Artnet (Jan. 12, 2018), available at https://news.artnet.com/exhibitions/art-lovers-demand-refund-fake-modigilani-exhibition-1197245. ↑

- Francesca Barra, The Piero Manzoni Foundation and the destruction of 39 works, Art@Law (2018), available at https://www.artatlaw.com/archives/2018-july-dec/piero-manzoni-foundation-destruction-39-works. ↑

- Casone, supra note 10. ↑

- Naomi Rea, Italian Police May Have Solved the Mystery of Who Was Behind an Exhibition of Fake Modigliani Paintings in Genoa, Artnet (Mar. 14, 2019), available at https://news.artnet.com/art-world/fake-modigliani-paintings-1488106. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Editorial Board, Falsi Modigliani, nuovi indagati, Genova Today, Cronaca (Mar. 13, 2019), available at https://www.genovatoday.it/cronaca/modigliani-chiusura-indagini.html. ↑

- Paula Marantz Cohen, The Meanings of Forgery, 97 Sw. Rev. 12, 13 (2012), available at www.jstor.org/stable/43821007, 14. ↑

- Max Horberry, The Artist Beneath the Art Forger, The New York Times (Feb. 21, 2020), available at, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/21/arts/design/elmyr-de-hory-art-forgery.html. ↑

- Alfred Lessing, What Is Wrong with a Forgery?, 23 J. Aesthetics and Art Criticism 461, 462–463 (1965). ↑

- Cohen, supra note 20, at 19 (quoting Alfred Lessing). ↑

- See id. ↑

- Ross Bowden, What Is Wrong with an Art Forgery?: An Anthropological Perspective, 57 J. Aesthetics and Art Criticism (1999), 334. ↑

- Lessing, supra note 25, at 464. ↑

- See id. ↑

- Cascone, supra note 10. ↑

- Frances D’Emilio, Italy: Modigliani art exhibit found to be full of fakes, The Denver Post (Jan. 10, 2018), available at https://www.denverpost.com/2018/01/10/amedeo-modigliani-italy-art-exhibit-fake/. ↑

- Bowden, supra note 24, at 334 (quoting Mark Jones). ↑

- Cascone, supra note 10. ↑

- Barra, supra note 12. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Cristina Ruiz and Ada Masoero, Piero Manzoni Foundation criticised for destruction of works, The Art Newspaper, (Apr. 4, 2018), available at https://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/piero-manzoni-foundation-criticised-for-destruction. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Articolo 178, Decreto Legislativo 42/2004, in G.U. 24 febbraio 2004, n.45 (It.). ↑

- Peter Barry Skolnik, Art Forgery: The Art Market and Legal Considerations, 7 Nova L. Rev. 315, 331 (1983), available at https://nsuworks.nova.edu/nlr/vol7/iss2/4. ↑

- Cascone, supra note 10. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Caroline Mortimer, Modigliani art exhibited at Ducal Palace in Genoa revealed to be almost entirely fake, Independent (Jan. 12, 2018), available at https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/art/news/italy-modigliani-fake-show-police-investigation-art-genoa-a8154701.html. ↑

- Editorial Board, Genoa Modigliani paintings are fake (4), ANSA: Arts Culture & Style (Jan. 9, 2018), available at https://www.ansa.it/english/news/lifestyle/arts/2018/01/09/genoa-modigliani-paintings-are-fake-4_c45accb7-d0b3-4bdf-b02e-0a30352bda73.html. ↑

- Skolnik, supra note 41, at 329. ↑

- Lawrence Scott Bauman, Legal Control of the Fabrication and Marketing of Fake Paintings, 24 Stan. L. Rev. 930, 941 (1972). ↑

- Skolnik, supra note 41, at 332. ↑

- Id. at 329. ↑

- Horberry, supra note 23. ↑

- Eileen Kinsella, Authenticating Modigliani Is Big Business. That’s Why One Expert Is Suing an Organization That Wants to Put Research Online for Free, Artnet (June 10, 2020), available at, https://news.artnet.com/art-world/modigliani-expert-sues-wildenstein-plattner-institute-1883370?utm_content=buffer6f82c&utm_medium=social&utm_source=facebook.com&utm_campaign=news. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Restellini v. The Wildenstein Plattner Institute, Inc., No. 1:20-cv-04388 (S.D.N.Y. filed on June 9, 2020). ↑

- Cohen, supra note 17, at 22. ↑

List of additional/suggested works:

- Cebik, L. B. “On the Suspicion of an Art Forgery.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 47, no. 2 (1989): 147-56. doi:10.2307/431827.

- Fleming, Stuart. “Art Forgery: Some Scientific Defenses.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 130, no. 2 (1986): 175-95. www.jstor.org/stable/987180.

- Mondini, Dania, and Claudio Loiodice. L’affare Modigliani. Prima edizione. Milano: Chiarelettere, 2019.

- Rush, Laurie, and Luisa Benedettini Millington. “Fakes, Forgeries and Money Laundering.” In The Carabinieri Command for the Protection of Cultural Property: Saving the World’s Heritage, 141-52. Rochester, NY, USA: Boydell & Brewer.

About the Author: Tatyana Kalaydjian Serraino is an Italian-Danish-Armenian art historian. She holds a BA from the University of Cambridge (St John’s College) and an MA from John Cabot University in Rome. She currently lives in London. She can be reached at https://cambridge.academia.edu/TatyanaKalaydjianSerraino.

Disclaimer: This article is for educational purposes only and is not meant to provide legal advice. Readers should not construe or rely on any comment or statement in this article as legal advice. For legal advice, readers should seek an attorney.

You must be logged in to post a comment.