Rolling Over in Her Grave: Frida Kahlo’s Trademarks and Commodified Legacy

August 2, 2019

By Laurel Wickersham Salisbury.

Art both creates and possesses cultural value, but this value can also be monetized, and, increasingly in today’s society, commercialized. This is especially true of iconic artists such as Frida Kahlo, Pablo Picasso, Andy Warhol and the like whose personal identities have become as instantly recognizable as their art. From Mattel’s Inspiring Women™ Barbie® doll of Kahlo to National Geographic’s ‘Genius: Picasso’ television series and fashion brand Alice and Olivia’s ‘collaborations’ with Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring, opportunities are plentiful for licensing the various rights in the “suite” or “bundle” of intellectual property rights. This creates moral and legal issues when an artist is deceased and control falls into the purview of the artist’s estate. Family members or foundations established in the artist’s name inherit the copyrights, trademarks, and, if applicable, the right of publicity. As evidenced by the recent controversies involving the Frida Kahlo Corporation, complications may arise when multiple parties must confer as to how best to continue the artist’s legacy.

While intellectual property rights have distinct purposes, together, they work to protect both the creator and the consumer. Copyright law exists to incentivize creation by offering to a creator exclusive control over their works for a statutory time period.[1] The period of protection varies from country to country and from type of protected content; in general, in the U.S., copyright lasts for the duration of the artist’s lifetime and for 70 years post mortem. In Mexico, however, copyright now lasts for 100 years after the artist’s death, but artists who died before 1956 (think: Frida Kahlo) received only 20-25 years of post mortem copyright protection.[2] Once a work of art of sufficient originality and creativity is fixed in a tangible medium, the copyright is automatically vested in the artist.[3]

Trademark law, on the other hand, purports to exist for the protection of the consumer and the investor. Based on the assumption that established brands have value, trademarks can be registered for an identifying word, symbol, or phrase for the purpose of differentiating certain products from others.[4] To qualify for trademark protection, the registrant must be able to demonstrate (1) use in commerce, and (2) distinctiveness.[5] In some cases, trademark protection can also be awarded to artists. Personal names “can receive trademark protection only if they’ve become descriptive and have acquired a secondary meaning.”[6] For example, an artist like Frida Kahlo or Pablo Picasso, whose artistic talent and tenacity led to critical acclaim and worldwide recognition, “has become a brand that can be applied at will.”[7] In recognition of this and the fact that “[e]veryone wants a piece of [the artist],”[8] it can make both protective and economic sense for an artist’s heirs or estate foundation to trademark the artist’s name because it has come to mean something and their signature serves as an emblem of artistry and quality. As once expressed by Picasso’s heirs, “[i]f we don’t use it, someone else will,”[9] and thus, if there is an interest in protecting the artist’s legacy, licensing opportunities must be controlled. The avenue for such control is often through trademark registration.

On Frida Kahlo: the Family, the Corporation, and the Controversies

Trademark registration does not always end the battle as the family of the late, Mexican surrealist artist Frida Kahlo (“Frida” or “Kahlo”) has recently learned. When Kahlo passed away in 1954, childless, she was survived by her husband, artist Diego Rivera, and her extended family (“the Family” or “the Kahlo family”). Because Kahlo died without a will, a.k.a. intestate,[10] per Mexico’s property law, the artist’s industrial property rights[11] were inherited by Frida’s niece, Isolda Pinedo Kahlo (“Isolda”).[12] Decades later, in 2003, Mara Cristina Romeo Pinedo (“Mara”), Isolda’s daughter, was granted power of attorney over her mother’s legal affairs, including the rights to Frida’s name and likeness.[13] Since Kahlo died in Mexico, Mexican law dictates the post mortem rights possessed by her heirs. There, the right of publicity – the right to control the use of one’s image and likeness – is retained for fifty years after one’s death.[14]

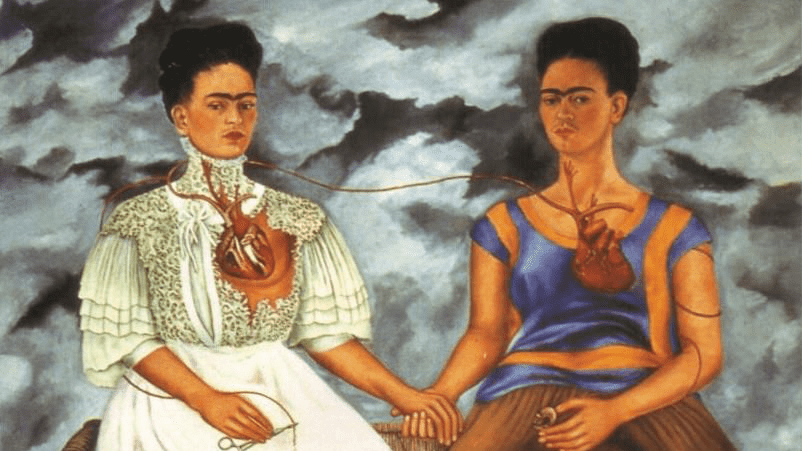

This right is especially important for someone like Frida Kahlo whose recognition stems largely from her distinctive appearance that served as the subject matter for much of her art. However, Frida’s right of publicity expired in 2004, so, the Family turned to trademark protection. The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office has records of registration of the “Frida Kahlo” name for use in a wide variety of commercial circumstances from as early as 2002; these initial registrations belonged to Isolda.[15] Then, around 2004, the Frida Kahlo Corporation (“FKC” or “the Corporation”) was formed “with the primary objective of licensing and commercializing the ‘Frida Kahlo’ brand worldwide,” and “with the mission to educate, share and preserve Frida Kahlo’s art, image, and legacy through the worldwide commercialization and licensing of the Frida Kahlo brand.”[16]

The establishment of the Corporation is where things become complicated – and, not to mention, a bit ironic considering Frida Kahlo’s beliefs and communist associations during her lifetime. The Kahlo family, namely Isolda and Mara, joined forces with Venezuelan businessman Carlos Dorado (“Dorado”). Reportedly, Dorado first learned of Frida Kahlo in 2002 and soon met members of the Kahlo family, with whom he entered into a partnership to form FKC, under the laws of Panama.[17] Dorado and Kahlo family members were shareholders to the Corporation; Mara even served as a director to FKC.[18] Mara, on behalf of her mother, legally transferred the existing U.S. trademark registrations to FKC; all subsequent U.S. registrations of Frida’s name, signature, initials, and slogans were registered directly by FKC.[19]

While most of the trademark holdings in Mexico are also registered to FKC, there are exceptions: one registration is held in Mara’s name, and another in the name of the “Familia Kahlo” company.[20] In late 2018, thirty-one new trademark registrations were granted to Mara.[21] The family maintains that pursuant to an internal agreement, the Corporation was not to make any licensing agreements or other decisions regarding the use of Frida’s name and signature without the approval of the Kahlo family.[22]

The Downfall: Frida Kahlo Corporation v. Mara Cristina Romeo Pinedo

In 2011, the working relationship between FKC (a.k.a. Dorado) and the Kahlo family, particularly Mara, began to dissolve.[23] The parties’ disagreements subsequently came to a head in the form of multiple lawsuits. Much of the recent tension seems to have originated with, or was at least aggravated by, the early-2018 debut of Mattel’s Frida Kahlo Barbie® as a part of their Inspiring Women™ series. The Barbie doll had the effect of publicly pitting FKC and the Kahlo family against one another. Mattel maintained that they worked closely with FKC to develop an authentic representation of Frida, while the Family expressed their disapproval of the doll for its commodified version of Frida’s appearance that lacked authentic dress and the artist’s signature unibrow, among other defining characteristics.[24] The Family pursued their grievances in court in Mexico, claiming the Corporation had exceeded their rights in licensing the use of Frida’s name without the family’s approval. The Court agreed and a temporary injunction was issued to stop Mattel’s sales of the doll in Mexico; yet, sales in the U.S. were unaffected. The Family, which controls the social media accounts under Frida Kahlo’s name, posted a letter addressed to the public, written in Spanish and English, stating that a decree was issued against FKC requiring the Corporation to refrain from (1) use of “the brand, image and work” of Frida Kahlo without the Family’s consent, and (2) “any act tending to commercialize products that have the brand and image of Frida Kahlo.”[25] In response, FKC brought suit against Mara and her daughter, Mara de Anda Romeo (“Romeo”).[26]

The Corporation asserted a number of claims including trademark infringement and unfair competition under the Lanham Act and commercial defamation.[27] FKC claims it is the absolute owner of all trademark rights to the Frida Kahlo name in the U.S., EU, and Mexico, and alleges that Mara has “embarked on a campaign to misappropriate the rights” now held by FKC “in order to profit at FKC’s expense and detriment.”[28] FKC maintains that the trademarks are valid because they are “distinctive” and “famous,” and claims that Mara’s use of the trademarks on the Frida Kahlo social media pages and website constitute infringement.[29] FKC also claims Mara’s public notices against FKC are slanderous and harmful to the brand, and constituted tortious interference with a business relationship, primarily FKC’s relationship with Mattel.[30] The Corporation sought compensatory damages for an amount greater than $75,000, a declaration naming FKC as the proper and sole owner of the Frida Kahlo trademarks, and multiple injunctions against Mara requiring the surrender of the website and social media pages and requiring her to refrain “from making further false statements.”[31]

Although FKC asserted proper venue, subject matter jurisdiction, and personal jurisdiction over the defendant in the Southern District of Florida on the basis of business activity in the jurisdiction, the Corporation has so far been unable to serve process on the defendants. On July 9, 2018, the Court granted FKC’s motion for an extension of time to serve process, and stayed and administratively closed the case pending completion of service of process. On January 9, 2019, FKC filed a report with the Court stating the petition of service had been properly received by legal authorities in Mexico to effectuate service. As of July 2019, the case has not been reopened.[32]

Frida Kahlo Corporation v. VersaLicensing

On June 3, 2019, FKC initiated another lawsuit, this time against the Mexican corporation VersaLicensing and its CEO, Jaime Meschoulam (“Meschoulam”).[33] The suit alleged contributory trademark infringement, false designation of origin, false advertisement, and unfair competition under the Lanham Act and common law. In this complaint, FKC alleges that Mara and Romeo, have together and under their company, “Familia Kahlo,” “embarked on a campaign to misappropriate the rights” owned by FKC.[34] As a part of that “campaign,” FKC alleges, the Family “engaged [VersaLicensing] to further their plan of undermining the legitimacy and validity of the FKC Trademarks.”[35] FKC claims VersaLicensing, on its website and through promotional materials, purported to represent the trademark of Frida Kahlo’s signed initials, “FK,” a trademark which is registered to FKC in the U.S.[36] The “FK” brand has since been removed from VersaLicensing’s website. As for relief, FKC again seeks compensatory damages in an amount greater than $75,000, a declaration that FKC is the proper trademark holder, and injunctions against VersaLicensing’s continued use of, or association with, the Frida Kahlo name and brand.[37]

On July 16, 2019, the defendants responded by filing a Motion to Dismiss for Failure to State a Claim and Lack of Personal Jurisdiction under Federal Rules of Civil Procedure 12(b)(6) and 12(b)(2), respectively.[38] Most importantly, in its Motion, VersaLicensing claims that its services were solicited by the Familia Kahlo to represent and license the brand only in Mexico, where Mara and the Familia Kahlo do possess trademark registrations separate from FKC.[39] VersaLicensing’s response also notes the ongoing litigation between FKC and the Kahlo family in Mexico on the matter of who rightfully owns the trademarks there.[40]

Nina Shope v. Frida Kahlo Corporation

The third ongoing case involving the Frida Kahlo Corporation was brought on June 5, 2019 by Colorado folk-artist Nina Shope (“Shope”).[41] She filed suit against FKC in response to the Corporation’s May 27 submission of a “notice of intellectual property infringement” to online arts and crafts retailer Etsy, where she sells her creations. Shope handmakes a variety of embroideries and dolls, many of which represent Frida Kahlo and are sold using her name. FKC submitted the notice against several of Shope’s dolls, which resulted in an automatic removal of those listings.[42] In Shope’s complaint against FKC, she asserts that her creations do not constitute trademark infringement. Shope also complained of “tortious interference with prospective business advantage” and “deceptive and unfair trade practices.”[43] She notes that the right of publicity to Frida’s image expired in 2004, and while the name “Frida Kahlo” is a registered trademark belonging to FKC, her use of Frida’s name is merely descriptive of the subject matter of her creations.[44] Furthermore, she asserts that the use of the name in conjunction with the doll is not “source-identifying,” essentially claiming, because the name is used to identify a historical figure, consumers would not assume the dolls are associated with the Corporation.[45] For protection, Shope relies on Fair Use and the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution;[46] she also cites the Mexican court’s temporary injunction against FKC’s use of the trademarks and alleges that FKC had knowledge, at least since May 2018, that creation of dolls in the likeness of Frida Kahlo is not an infringing use.[47] Among the relief sought is an order declaring non-infringement and damages in the amount of lost revenues.[48] Additionally, Shope calls for the U.S. trademark registration currently owned by FKC over the use of the name “Frida Kahlo” in the category of ‘dolls’ to be cancelled because it is generic and purely functional.[49]

On July 22, 2019, FKC responded to Shope’s complaint with a Motion to Dismiss for Lack of Personal Jurisdiction and Improper Venue, and, in the alternative, a Motion to Transfer the suit to the Southern District of Florida. FKC also moved to strike certain allegations from the complaint under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(f) on the basis that they are “impertinent, immaterial, or scandalous.”[50]

FKC or “Further Kahlo Commodification”

The international controversy, public backlash, and onslaught of lawsuits have not slowed down the Frida Kahlo Corporation as it continues to debut commercial collaborations.

First, in June of 2019, in conjunction with the Corporation, the sneaker company Vans debuted a collection of Frida Kahlo sneakers – each of the three pairs features a different Frida Kahlo painting, two of which are self-portraits. The website and promotional materials for the shoe collection feature the registered “Frida Kahlo” signature. Per Mexican law, use of Kahlo’s artworks is permissible without the Family’s permission as the works entered the public domain 25 years after the artist’s death. There has not been widespread negative public response to the shoe collection, though the extensive series of material commodities showcasing her artwork would no doubt have Frida rolling over in her grave once more, and the Kahlo family is likely to be against the collaboration as it goes against the Mexico court’s decree ordering FKC to refrain from use of the trademarks in commerce.

Second, in early July 2019, Ulta Beauty launched a makeup collection in collaboration with FKC. The collection of nine beauty products contains an eyeshadow palette featuring bold and bright shadow colors, a cosmetics bag, and, fittingly, a “brow master palette.” This collaboration, however, created another public outcry, reminiscent of the 2018 Barbie, because the images of Frida featured on the collection’s packaging have downplayed her unibrow and upper-lip hair, two defining facial characteristics for which Frida has come to be known and celebrated.

Not just a name?

While no true conclusions can be drawn from the ongoing lawsuits just yet, it will be interesting to see how both the U.S. and Mexican courts rule on the questions asked by these cases. In particular, as raised by Nina Shope’s complaint against FKC, is an artist’s name always eligible for trademark protection, even when used in a merely descriptive manner? The controversies also beg questions of morality. The commercial exploitation of an artist’s name and legacy seems, at times, ignoble or, at least, dubious, especially in the case of an artist like Frida Kahlo, who was known to be ideologically opposed to the consumerism her name is now endorsing.

Sources:

- The holder of a copyright has the exclusive right to reproduce, distribute, publicly display or perform, and create derivatives of the original work. See The Copyright Act of 1976, post note 3. ↑

- The different lengths of Copyright in Mexico, Reyes Fenig Asociados – Intellectual Property (Apr. 17, 2014). ↑

- The Copyright Act of 1976, 17 U.S.C. § 101, et seq., (1976). ↑

- The Lanham Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1051, et seq., (1946). (NB: At least in the U.S., the copyright must still be registered with the Copyright Office in order to receive monetary damages from an infringement in a court of law.) ↑

- Trademark Law: Everything You Need to Know, upcounsel.com. ↑

- Id. ↑

- See Milton Esterow, Battle for Picasso’s Multi-Billion-Dollar Empire, Vanity Fair (Mar. 7, 2016) (quoting Jean Clair in Libération (1998)). ↑

- Id., (quoting Eric Mourlot). ↑

- Jessica Meiselman, From Picasso’s Signature to Kahlo’s Unibrow, Who Legally Owns the Rights to an Artist’s Brand?, artsy.net (Jun. 5, 2018) (quoting Jean-Jacques Neuer, counsel to Claude Picasso). ↑

- To die “intestate” means without a will. ↑

- ‘Industrial Property Rights’ is the term used in Mexico for the rights which are roughly equivalent to intellectual property rights in the U.S. ↑

- Complaint at 3, Frida Kahlo Corp. v. Romeo Pinedo, 1:18-cv-21826 (S.D. Fla. filed May 7, 2018). ↑

- Id. at 4. ↑

- Right of Publicity in Mexico, Uhthoff Gomez Vega & Uhthoff SC for Lexology. (NB: The right of publicity is also recognized in most U.S. jurisdictions, but exists post mortem in only a few; for example, California does recognize the right, but New York does not. The rights received are determined by place of death. See Judith B. Prowda, Visual Arts and the Law, 41 (2013).) ↑

- See, e.g., FRIDA KAHLO, Registration Nos. 2999526, 3047286, 3318902, 3318903, 3326314, 3326313. ↑

- Complaint at 4, Frida Kahlo Corp. v. VersaLicencing, 1:19-cv-22258 (S.D. Fla. filed June 3, 2019). ↑

- Amended Complaint at 6, Shope v. Frida Kahlo Corp., 1:19-cv-01614 (D. Colo. filed June 5, 2019). ↑

- Complaint at 3, Frida Kahlo Corp. v. Romeo Pinedo, supra note 11. ↑

- See, e.g., FRIDA KAHLO, Registration Nos. 2999526, 3047286, 3318902, 3318903, 3326314, 3326313. See also, FRIDA KAHLO, FK, etc., Registration Nos. 3437962, 3437963, 3437964, 3787499, 3799598, 4578719, 4739999, 5351310, 5341582, 5633311, 5784451, 5788116, 5186539, 5700393, 5754785. ↑

- Mex. Trademark Search, FRIDA KAHLO, Marcaria.com (last accessed July 25, 2019). (NB: “Familia Kahlo, S.A. de C.V.” is a Mexican company owned and operated by Mara Cristina Teresa Romeo Pinedo and her daughter Mara de Anda Romeo. See Complaint at 9, Frida Kahlo Corp. v. VersaLicencing, supra note 10.) ↑

- See Mex. Trademark Search, FRIDA KAHLO, Marcaria.com (After the controversy involving Mattel’s Inspiring Women Frida Kahlo Barbie, Mara Cristina Teresa Romeo Pinedo filed for thirty-one new trademark registrations for the name ‘Frida’ and related aliases in a variety of registration classes; the trademark registrations were granted to her on Aug. 8, 2018.) ↑

- Amended Complaint at 6, Shope v. Frida Kahlo Corp., supra note 16. ↑

- Complaint at 5, Frida Kahlo Corp. v. Romeo Pinedo, supra note 11. ↑

- Patrick J. McDonnell, Mattel has a new doll: Frida Kahlo Barbie. Descendants of the artist want it off the shelves, Los Angeles Times (Mar. 9, 2018). ↑

- Frida Kahlo (@FridaKahlo), Twitter (Apr. 18, 2018, 8:08 PM). ↑

- See First Amended Complaint, Frida Kahlo Corp. v. Romeo Pinedo, supra note 11. ↑

- Complaint at 1, Frida Kahlo Corp. v. Romeo Pinedo, supra note 11. ↑

- Id. at 5. ↑

- Id. at 6, 12. ↑

- Id. at 16. ↑

- Id. at 17-18. ↑

- See Civil Docket Report, Ct. Doc. Nos. 13, 15, Frida Kahlo v. Romeo Pinedo, supra note 11. ↑

- Frida Kahlo Corp. v. VersaLicencing, supra note 15. ↑

- Complaint at 9, Frida Kahlo Corp. v. Versalicencing, supra note 15. ↑

- Id. at 10. ↑

- Id. at 10-13. ↑

- Id. at 27-28. ↑

- Defendants’ Motion to Dismiss at 2, Frida Kahlo Corp. v. VersaLicencing, supra note 15. ↑

- Id. at 2-3. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Shope v. Frida Kahlo Corp., supra note 16. ↑

- Amended Complaint at 8, Shope v. Frida Kahlo Corp., supra note 16. ↑

- Id. at 2. ↑

- Id. at 9. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. at 10. ↑

- Id. at 6-7, 8. ↑

- Id. at 16. ↑

- Id. at 12-13. ↑

- Defendant’s Motion to Dismiss, Motion to Transfer, and Motion to Strike, Shope v. Frida Kahlo Corp., supra note 16. ↑

About the Author: Laurel Wickersham Salisbury is a Summer 2019 Legal Intern at the Center for Art Law. She is a J.D. candidate at Duke University School of Law, Class of 2021. She holds her B.A. in Art History from Emory University (2015), and a M.A. in Art Business from Sotheby’s Institute of Art, Los Angeles (2017). Laurel can be reached at laurel.salisbury@lawnet.duke.edu.

Disclaimer: This article is for educational purposes only and is not meant to provide legal advice. Readers should not construe or rely on any comment or statement in this article as legal advice. For legal advice, readers should seek a consultation with an attorney.

You must be logged in to post a comment.