Updates from the Video Game World: The Copyright Issues of Realistic Gameplay

June 22, 2020

By Christopher Zheng

From living room couches to massive conventions, video games dominate our entertainment culture. Today, the incredible market value and ubiquitous presence of video games are undeniable. In 2018, total video game sales topped $43.4 billion, and 164 million people, or 65% of adults in the United States, reported playing video games. [1] In the legal field, the rise of eSports (players who compete in video games for profit while fans watch) has created unique issues surrounding player endorsements, contracts, and intellectual property disputes over ownership of gameplay footage.[2] In fact, in 2017, a Seattle attorney established the first eSports-only law firm, and many firms have since followed suit by creating their own eSports practice groups.[3]

To create such successful products, video game companies assemble teams of concept artists, animators, engineers, and programmers to bring their visions to the screen. This process of creation necessarily involves copyright concerns over the concepts and designs of each game. Recently, two cases decided in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York illustrated the complex copyright issues involved when video games reproduce copyrighted material. Both cases are illustrative of the representational dilemma of video games that seek to mirror the real world: try to be as realistic as possible and risk infringing on existing copyrights or play it safe but lose gamers seeking the most realistic visuals.

The Art of Video Games

While those who avidly enjoy gaming would likely find the artistic merits of video games to be obvious, there are many who might scoff at such an idea. However, major players in the art world have long accepted video games into their galleries. For instance, the Smithsonian American Art Museum hosted the exhibition “The Art of Video Games” in 2012, celebrating “the phenomenal evolution of the mediums art and design…”[4] The same year, the Museum of Modern Art announced the acquisition of 14 video games for its permanent collection, including classics like Pac-Man (1980) and Tetris (1984) as well as more modern additions like EVE Online (2003) and Portal (2007).[5]

Curators are not alone in their acceptance. In 2011, the Supreme Court held in Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Association that video games contained many of the same qualities as other artistic media and were thus entitled to the same First Amendment protections: “like the protected books, plays and movies that preceded them, video games communicate ideas – and even social messages – through many familiar literary devices (such as characters, dialogue, plot and music) and through features distinctive to the medium (such as the player’s interaction with the virtual world).”[6]

Use of Copyrighted Material in Video Games

By establishing video games’ artistic qualities, the court also implicitly recognized their significant interactions in the realm of copyright. While video games are copyrightable themselves, there are pressing questions raised in determining the extent to which video games may use other copyrighted material. In reproducing a real world setting or activity, some elements of video game artwork are not copyrightable “to the extent that they are necessary to execute a particular genre of work.”[7] This doctrine, known as scenes à faire, denies copyright protection to “expressions that are standard, stock, or common to a particular topic, or that necessarily follow from a common theme or setting.”[8] As such, a basketball video game could not copy material from another basketball video game, but could freely use standard design elements like the court, hoops, and balls.

The U.S. Copyright Office has explained the boundaries on copyright protection for video games, stating “[c]opyright does not protect the idea for a game, its name or title, or the method or methods for playing it.”[9] As such, elements such as the games’ rules and mechanisms are not protectable.[10] However, infringement claims are permissible where copyrighted works are used without authorization in a game. Thus, the more difficult questions arise where a game depicts, say, a specific car manufacturer’s armored truck or an artist’s tattoo on a celebrity’s arm.

Case Study I: AM General, LLC v. Activision Blizzard Inc. (2020)

Call of Duty has been the best-selling console franchise in the United States for over a decade,[11] entertaining players with action-packed simulations of modern warfare. Industry experts believe that the franchise’s success is attributable to its “unmatched level of verisimilitude…created through the use of real-world settings, weapons, uniforms, units, and vehicles…”[12] One such vehicle is an armored truck known as a Humvee, short for High Mobility Multipurpose Wheeled Vehicle, which has become an icon of the American military after three decades of use. [13] Humvees are manufactured by AM General (“AMG”) which also controls licensing of the Humvee’s design and trademarks to other parties such as toy manufacturers or video game companies.[14] Therein lay the central issue of this case: Call of Duty had not received any permission or licensing to use the Humvee design, but had featured the truck 228 times throughout its gameplay.[15]

An all-terrain military vehicle known as a Humvee, manufactured by AM General. Image Source: Figure 3 from Compl., 6, Nov, 17, 2017, 1:17-cv-08644-GBD.

A screengrab of a Humvee from the best-selling video game Call of Duty.

Image Source: Figure 11 from Compl., 16, Nov. 7, 2017, 1:17-cv-08644-GBD.

AMG filed suit for compensatory and punitive damages on claims of trademark infringement, trade dress infringement, unfair competition, false designation of origin, false advertising, and mark dilution under the Lanham Act.[16] The court ultimately granted Activision’s motion for summary judgement on each claim,[17] meaning the court found no “genuine issue of material fact” such that a “reasonable jury could return a verdict for the nonmoving party [AMG].”[18]

On the claims related to fair business practices, AMG failed to offer sufficient evidence indicating damage to its Humvee mark. Addressing trademark infringement, the court first considered the artistic relevance of Activision’s use of the Humvee, acknowledging that “featuring actual vehicles used by military operations around the world in video games about simulated modern warfare surely evokes a sense of realism and lifelikeness…”[19] Secondly, the court applied the Polaroid factors, an eight factor test assessing consumer confusion, by which the court considers 1) strength of the mark, 2) degree of similarity in two mark uses, 3) proximity of products in the marketplace, 4) likelihood that the mark owner will bridge the gap, 5) evidence of actual confusion, 6) defendant’s good faith in adopting the mark, 7) quality of the defendant’s product, and 8) sophistication of consumers.[20] The court found that all but the first and fifth factors favored Activision, and that the non-dispositive factors in favor of AMG were outweighed by free speech protections.[21] Furthermore, analysis on the other claims of unfair competition, false designation of origin, false advertising, and mark dilution follow tests identical or similar to the Polaroid factors, and thus the court did not find AMG’s evidence (or lack thereof) sufficient to prove consumer confusion.[22]

The Art of the Humvee

Of particular interest to artistic expression is the court’s opinion on the trade dress claim, a cause of action concerning the design or shape of a product’s packaging or the product itself.[23] In order to win on a trade dress claim, AMG had to succeed on three factors: (1) the claimed trade dress is non-functional, (2) has secondary meaning, and (3) there is a likelihood of confusion between the plaintiff’s and defendant’s goods.[24] Essentially, the tests attempt to discern if the material at issue is expressive rather than utilitarian and whether the average consumer might be misled by the defendant’s use of the plaintiff’s design or product. The court did not explicitly address the first two factors, assuming their validity arguendo, because the third factor on consumer confusion between a video game and “a full-blown military machine” was too improbable to rule in AMG’s favor.[25]

The court’s grant of summary judgement on all claims was rooted in balancing artistic license with consumer confusion, finding that the video game designers’ need to use real-world elements was an indispensable part of the medium. The opinion made clear that “if realism is an artistic goal, then the presence in modern warfare games of vehicles employed by actual militaries undoubtedly furthers that goal.”[26] A different outcome in favor of AGM may have opened the door to a plethora of lawsuits by car manufacturers whose vehicles are also reproduced throughout the games.

Case Study II: Solid Oak Sketches, LLC v. Visual Concepts, LLC (2020)

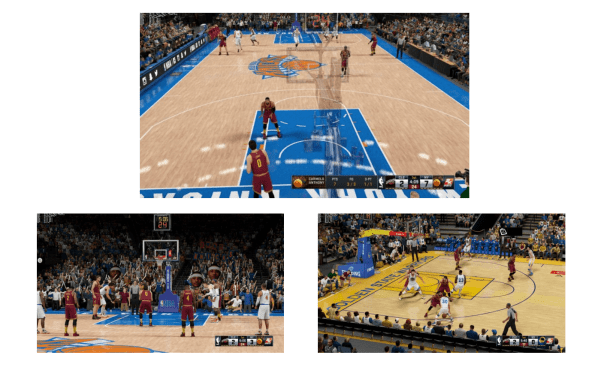

Screengrab of gameplay in NBA 2K. Source: Defendant’s Answer and Counterclaims, 28, Aug. 16, 2016, 1:16-cv-00724.

Sports-based video games thrive because of gamers who enjoy virtually taking the court as their favorite athletes. However, the appearance of a recognizable star player on screen is the product of a licensing agreement between players unions and video game publishers.[27] This licensing system is complicated when players’ likenesses feature material that is copyrighted by another party. In the case of Solid Oak Sketches, LLC v. Visual Concepts, LLC et al, a body art licensing company with exclusive copyrights on the tattoos of several basketball players like Lebron James filed suit against video game publisher Take-Two Interactive for its reproduction of those tattoos on virtual avatars in the NBA 2K series.[28]

The question of tattoos as copyrightable material is not a new challenge. In fact, Take-Two has been sued three times for the use of tattoos in sports video games from the NBA 2k series for basketball to WWE 2k for wrestling.[29] Under the Copyright Act, material is capable of copyright protection from the start of its existence as long as it is “fixed in any tangible medium of expression,”[30] meaning that content existing in physical form for some period of time qualifies. For instance, a choreographer can register a dance for copyright if it is captured on video or is explained in written detail because there is a physical representation of the dance. However, there is a grey area in the “fixed” requirement. For instance, in Kelley v. Chicago Park District, the court held that artist Chapman Kelley’s wildflower bed displays did not constitute a fixed work as understood under the Copyright Act.[31] However, regarding the validity of Solid Oak Sketches’ copyright on players’ tattoos, permanent ink on skin appears to fall well within the Act’s requirement for both “fixed” and “tangible” presentation.[32] Players unions recognize the potential copyright implications of tattoos and often advise players to proactively secure licensing agreements with tattoo artists, who often agree rather than pass up a celebrity client.[33] Even so, in the often imperfect chain of licensing between artists, players, and video game companies, disagreements over permitted use and the extent of use are sure to arise.

In the case at hand, after demand letters offering licensing for $819,000 per year went ignored, Solid Oak Sketches filed a claim of copyright infringement on February 1, 2016.[34] To win this claim, the plaintiff had to demonstrate that Take-Two 1) actually copied the tattoos and 2) there was substantial similarity between Take-Two’s use and Solid Oak’s copyrighted designs.[35] The defendants argued that the substantial similarity factor went in their favor because their use was de minimis and permissible because of an implied license.[36]

Left: “Child Portrait Tattoo Artwork”, completed in 2006 on LeBron James and registered with the Copyright Office on June 8, 2015. Right: NBA 2k16’s rendition. Source: Defendant’s Answer and Counterclaims, 57 and 67, Aug. 16, 2016, 1:16-cv-00724.

In Defense of the Use of Tattoos

The de minimis defense requires that a defendant’s use of copyrighted material falls below the “quantitative threshold” of substantial similarity, judged by 1) the amount of work that is copied, 2) the observability of the copyrighted work, and 3) factors such as “focus, lighting, camera angles, and prominence.”[37] The court agreed that Take-Two’s use fell far below this threshold for numerous reasons: the tattoos only appeared on their appropriate players, average gameplay was unlikely to feature the specific players with the tattoos at issue, the tattoos were small and indistinct, and the game’s camera angles and players’ quick movements distorted any tattoos into “visual noise.”[38] In fact, the court compared visible tattoos to a simulated player’s nose shape or hairstyle, finding them a necessary component of realistic depiction.[39] Lebron James echoed this thought in his written declaration of support for Take-Two, stating “[m]y tattoos are a part of my persona and identity…If I am not shown with my tattoos, it wouldn’t really be a depiction of me.”[40]

On the issue of implied license, the court noted that, while it did not yet have a precise test, it had previously granted implied licenses to works-for-hire where intent to copy and distribute was clear.[41] As such, the court ruled in favor of Take-Two in light of depositions demonstrating the tattoo artists’ knowledge that the players intended to distribute their tattoos by appearing in public and in commercial media.[42] The court further solidified this view by granting Take-Two’s fair use counterclaim, in which the four fair use standards [1) purpose and character of use; 2) nature of copyrighted work; 3) substantiality of portion used; 4) effect on market of copyrighted work] all went in favor of the defendants due to de minimis use and low risk of market substitution.[43] Ultimately, the court respected Take-Two’s full and naturalistic depiction of star athletes for the purpose of realistic gameplay, especially where the use of copyrighted material was only a blur of ink on a player making a free throw.

Implications for the Industry

In both cases examined, the court sided with video game designers, acknowledging the value of using copyrighted material in order to make a game as realistic as possible. As a result, video game artists can essentially follow the status quo. Those who wish to successfully challenge unauthorized use of their copyrighted works in video games face an uphill battle, in which they must prove excessive and unnecessary use unrelated to artistic expression.

Had the decisions gone the other way, however, the implications could have been notable. If the court required Activision to get a license, game creators would have to be much more cautious in their use of trademarked or copyrighted material, and their insurers might “expand exclusions or increase premiums for infringement coverage.”[44] And if the court required Take-Two Interactive to obtain licensing for players’ tattoos, despite already getting likeness licenses from the NBA,[45] such vague precedent might allow a “tattoo artist to, essentially, control the use or portrayal of a person’s body [which] would be an absurd outcome.”[46] But seeing as the court in both cases ruled in favor of the game companies, it is clear more than ever that the recognition of video games as art makes their expression worth protecting.

Endnotes:

- ESA, 2019 Essential Facts About the Computer and Video Game Industry, Entertainment Software Association (May 2019), https://www.theesa.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/ESA_Essential_facts_2019_final.pdf. ↑

- eSports Law Growth, USC Gould Online Blog, https://onlinellm.usc.edu/blog/esports-law-growth/ (last accessed Jun. 6, 2020). ↑

- Patrick J. McKenna, eSports Practice Becoming a Lucrative Micro-Niche for Law Firms, Thomson Reuters Leg. Exec. Inst. (Mar. 28, 2019), https://www.legalexecutiveinstitute.com/micro-niche-esports-practice/#:~:text=eSports%20Practice%20Becoming%20a%20Lucrative%20Micro%2DNiche%20for%20Law%20Firms,-Patrick%20J.&text=For%20the%20uninformed%2C%20eSports%20law,that%20come%20with%20those%20arrangements. ↑

- Catherine Jewell, Video Games: 21st Century Art, World Intellectual Property Organization (Aug. 2012), https://www.wipo.int/wipo_magazine/en/2012/04/article_0003.html. ↑

- Paola Antonelli, Video Games: 14 in the Collection, for Starters, Museum of Modern Art: Inside Out Blog (Nov. 29, 2012), https://www.moma.org/explore/inside_out/2012/11/29/video-games-14-in-the-collection-for-starters/. ↑

- Brown v. Entm’t Merchs. Ass’n, 564 U.S. 786, 790 (2011). ↑

- Jewell, supra note 4. ↑

- Gates Rubber Co. v. Bando Chem. Indus., Ltd., 9 F.3d 823, 838 (10th Cir. 1993). ↑

- U.S. Copyright Office, FL-108, Games (reviewed Apr. 2016), available at https://www.copyright.gov/fls/fl108.pdf. ↑

- See generally Sonali D. Maitra, It’s How You Play the Game: Why Videogame Rules Are Not Expression Protected by Copyright Law, 7 Landslide 4 (Mar./Apr. 2015), available at https://www.americanbar.org/groups/intellectual_property_law/publications/landslide/2014-15/march-april/its_how_you_play_game_why_videogame_rules_are_not_expression_protected_copyright_law/. ↑

- Stephanie Fogel, ‘Call of Duty’ Is Best-Selling Franchise For 10th Consecutive Year, Variety (Jan. 25, 2019), https://variety.com/2019/gaming/news/call-of-duty-best-selling-10th-consecutive-year-1203118622/. ↑

- David C. Baker, Feature: Humvees, Video Games, Trademarks, and the First Amendment, 62 Orange County Lawyer 38, 39 (2020). ↑

- Id. at 39–40. ↑

- Id. at 40. ↑

- Law360, TM Rights Vs. Free Speech In Humvee Call of Duty Case, LexisNexis (Sept. 13, 2019), https://advance.lexis.com/api/permalink/ac74e61b-f07b-4158-a807-3bc7436e9d6a/?context=1000516. ↑

- AM Gen., LLC v. Activision Blizzard Inc., 2020 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 57121, at *2 (S.D.N.Y., Mar. 31, 2020). ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. at *6. ↑

- Id. at *16. ↑

- Trademarks: Demonstrating Actual Consumer Confusion, Cornell Law School (2010), available at https://courses2.cit.cornell.edu/sociallaw/topics/Trademarks-confusion.htm#:~:text=For%20example%2C%20in%20the%20Second,confusion%3B%20(6)%20defendant’s%20good. ↑

- See generally AM Gen., 2020 US Dist. LEXIS 57121 at *18–27. ↑

- See generally id at *32–36. ↑

- Trade Dress, Legal Information Institute: Wex, https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/trade_dress (last accessed on Jun. 4, 2020). ↑

- AM Gen., 2020 US Dist. LEXIS 57121 at *30. ↑

- Id. at *31. ↑

- Id. at *27. ↑

- Jason M. Bailey, Athletes Don’t Own Their Tattoos. That’s a Problem for Video Game Developers, N.Y. Times (Dec. 27, 2018), available at https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/27/style/tattoos-video-games.html. ↑

- See generally Solid Oak Sketches, LLC v. Visual Concepts, LLC et al., No. 1:2016cv00724 (S.D.N.Y. Mar. 26, 2020), available at https://dockets.justia.com/docket/new-york/nysdce/1:2016cv00724/452890. ↑

- Bailey, supra note 27. ↑

- 17 U.S.C. § 102 (2018). ↑

- See generally Kelley v. Chi. Park Dist., 635 F.3d 290 (7th Cir. 2011). ↑

- Roy Kaufman, Tattoos, Video Games And Questions Of Copyright Reuse, Copyright Clearance Center (Feb. 14, 2019), available at https://www.copyright.com/blog/tattoos-video-games-and-questions-of-copyright-reuse/. ↑

- Bailey, supra note 27. ↑

- Law360, Novel Suit Over Tattoos In Video Games Likely To Fade, LexisNexis (Feb. 8, 2016). ↑

- See Solid Oak Sketches, No. 1:2016cv00724 at 10. ↑

- See generally id. at 10–16. ↑

- Id. at 10–11 (quoting Sandoval v. New Line Cinema Corp., 147 F.3d 215, 217 (2d Cir. 1998)). ↑

- Id. at 13–14. ↑

- Id. at 7. ↑

- Bailey, supra note 25. ↑

- See Solid Oak Sketches, No. 1:2016cv00724 at 14. ↑

- Id. at 15. ↑

- See generally id. at 16–23. ↑

- Law360, TM Rights, supra note 15. ↑

- See Solid Oak Sketches, No. 1:2016cv00724 at 16. ↑

- Law360, Novel Suit, supra note 33 (quoting Jennifer Lloyd Kelly, a partner with Fenwick & West LLP). ↑

Further Reading:

- Samantha Elie, Whose Tattoos? Body Art and Copyright (Part I), Center for Art Law (Mar. 16, 2016), available at https://itsartlaw.org/2016/03/16/whose-tattoos-tattoos-and-copyright/.

- New Media Rights, Video Games and the law: Copyright, Trademark and Intellectual Property, New Media Rights (Nov. 19, 2018), available at https://www.newmediarights.org/guide/legal/Video_Games_law_Copyright_Trademark_Intellectual_Property.

- Shigenori Matsui, Does it have to be Copyright Infringement?: Live Game Streaming and Copyright, 24 Tex. Intell. Prop. L.J. 215 (2016).

- Thomas Hemnes, The Adaption of Copyright Law to Video Games, 131 U. Pa. L. Rev. 171 (Nov. 1982), available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/3311832?seq=1.

About the Author: Christopher Zheng is a Summer 2020 legal intern at the Center for Art Law. He is in the class of 2022 at Harvard Law School and graduated from Columbia University in 2019 with a B.A. in art history and political science. After working in nonprofit arts advocacy and arts education, he decided to focus on the intersections between art and law, with a particular interest in cultural heritage protections, art restitution, intellectual property in new media, and copyright issues. At Harvard, he serves as a senior articles editor for the Journal on Sports and Entertainment Law and is the vice president of fashion and fine arts programming for the Committee on Sports and Entertainment Law. You can reach him at czheng@jd22.law.harvard.edu.

Disclaimer: This article is for educational purposes only and is not meant to provide legal advice. Readers should not construe or rely on any comment or statement in this article as legal advice. For legal advice, readers should seek an attorney.

You must be logged in to post a comment.