How Artist Collective MSCHF Plays With The Law

June 7, 2021

By Laura Michiko Kaiser.

MSCHF (pronounced “mischief”) is a startup creative collective based in Brooklyn that produces artworks and designs in various formats including: social media channels, apps, browser plugins, and physical products. The collective, founded and led by Gabriel Whaley, is made up of artists, designers, and product developers whose goal is to “produce social commentary,”[1] push boundaries, make fun of certain industries, and decidedly not to make a profit.[2] MSCHF does not advertise on Instagram or Twitter, but rather notifies interested individuals about its “drops” (i.e. releases) via the MSCHF app.[3] MSCHFs’ works can be regarded as viral pranks or marketing campaigns—some of which have been (or could be) challenged on legal grounds. However, “running away with stuff” is what MSCHF does, according to Whaley.[4]

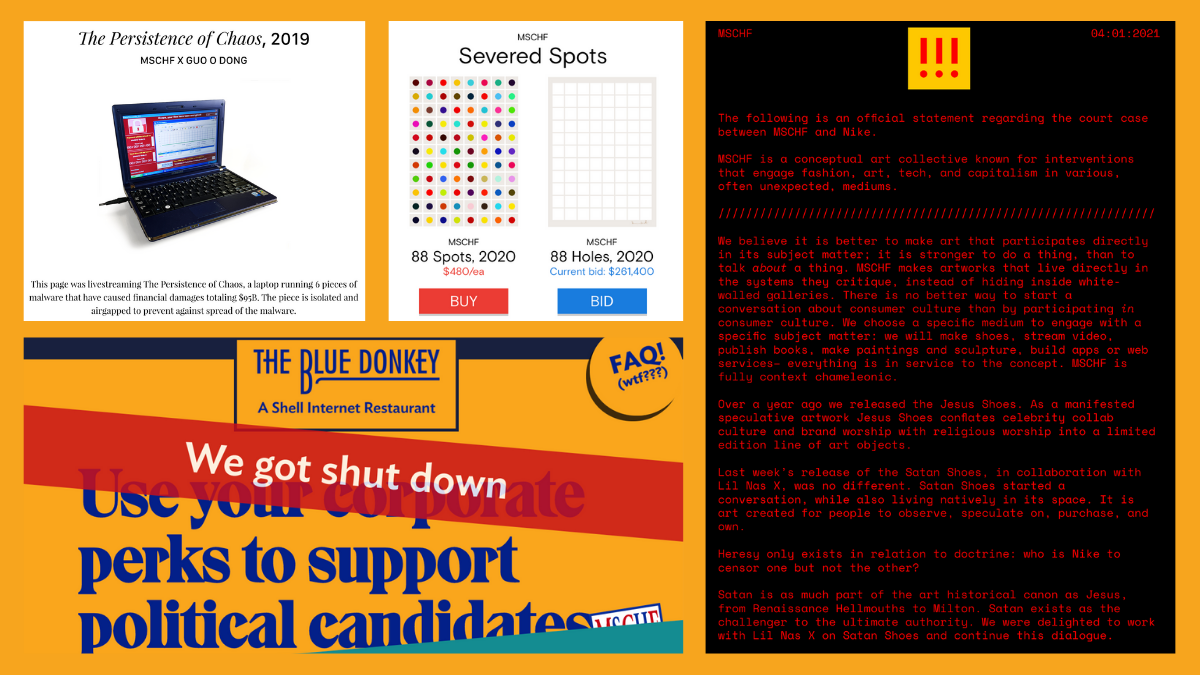

The collective’s first product, “The Persistence of Chaos,” was released in May 2019—a 2008 Windows laptop that ran six pieces of malware and was auctioned for over $1 million.[5] Another popular release was “Puff the Squeaky Chicken,” a rubber chicken that functions as a bong and squeaks when smoked. Later, MSCHF created a shell restaurant called “The Blue Donkey” that allowed individuals to order food through Grubhub/Seamless with their corporate perk discount cards in order to make a statement in opposition to big corporations––it was shut down. Instead of delivering food, the money was donated to a political candidate of the purchaser’s choice that may support anti-corporate policies.[6] A full list of MSCHFs’ drops, minus the “restricted” ones,[7] is available on their website. While there is a wide range of legal issues that could apply to the collective’s activities, the focus of this article are two projects that implicate intellectual property law.

“Severed Spots”

Readers of art news may remember drop #20 where MSCHF bought a limited print of a Damien Hirst spot painting, L-Isoleucine T-Butyl Ester, and cut it up, selling the individual 88 spots for $480 apiece.[8] The purpose of the piece was to criticize an art market practice whereby investors combine resources to buy artworks and then flip the works to another buyer or group of buyers.[9] Hirst did not bring a legal claim against MSCHF, but the question remains: could he have?

Screengrab from MSCHF’s “Severed Spots” project. Source.

Hirst is a British artist and L-Isoleucine T-Butyl Ester was created in 2018,[10] presumably in London as that is where Hirst’s studio is. Assuming that Hirst would file a federal suit in the U.S. (where MSCHF is based) and where Hirst is a national of a member of the Berne Convention, L-Isoleucine T-Butyl Ester should have U.S. copyright protection as a foreign work.[11] Additionally, foreign works do not need to be registered with the U.S. Copyright Office before an infringement lawsuit is filed.[12]

An additional question is whether the Visual Artists Rights Act (“VARA”) applies to Hirst because he is a non-U.S. national author. Under the Berne Convention, a domestic copyright holder and a foreign national must have the same protections.[13] Therefore, it seems that a UK artist suing for infringement in the U.S. should be afforded the same VARA rights a U.S. artist has.[14] VARA rights allow visual artists to sue in federal court when their art is intentionally distorted or mutilated in a way that is prejudicial to their reputation.[15] Because MSCHF lists Hirst’s name on the “Severed Spots” website, Hirst could also claim a VARA violation for using his name in connection with his mutilated artwork.[16] Further, Hirst could allege that L-Isoleucine T-Butyl Ester was a work of “recognized stature” that MSCHF destroyed.[17]

If Hirst wanted UK copyright law to apply and brought an action in the UK instead of the U.S., his moral rights would be slightly different.[18] In the UK, an artist can object to derogatory treatment of their work, but there is no moral right to prevent destruction of a work.[19] In both the U.S. and the UK, moral rights can be waived by the artist.[20] UK artists also rely on contract law to enforce their moral rights more than copyright law.[21]

In addition to VARA, other copyright law principles may apply. Artists have six exclusive rights to their works under copyright law, and if non-copyright holders exercise one of those rights without a license or permission the artist could claim a copyright violation.[22] The right to create derivative works, defined as transforming or adapting a work already in existence, could be relevant for “Severed Spots.”[23] However, MSCHF transformed the original print by cutting it into separate pieces (the individual spots and the frame), this type of creation does not fit under the traditional understanding of a derivative work, which oftentimes include a motion picture based on a play or novel, a drawing based on a photograph, or a new version of an existing computer program.[24]

However, even if faced with a copyright claim, the fair use defense could arguably protect MSCHF. Fair use analysis requires a balancing of four factors: the purpose and character of the use, the nature of the copyright work, the amount used in relation to the work as a whole, and the effect of the use on the potential market for the copyrighted work.[25] If challenged, MSCHF would probably focus on the first factor and the transformative nature of their piece. The U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York (“SDNY”) leans heavily into “transformation” and frequently finds fair use when the non-copyright holder’s purpose for the use is different from the copyright holder’s original intention.[26] MSCHF has made it clear that their purpose is to comment on and criticize the art market,[27] while Hirst’s spot paintings are titled with chemical or drug names (one group is called Controlled Substances)—presumably to make a statement on the artificiality and pervasiveness of drugs worldwide.[28] There is a good chance this work would be transformative enough for fair use, at least under SDNY precedent.[29] Despite VARA’s explicit language making it subject to the fair use defense, it is unclear how a court would analyze an interaction between fair use and a VARA claim.[30]

MSCHF’s activity might also be protected under the first sale doctrine—which provides that the owner of a work is allowed to sell or dispose of that copy without the copyright holder’s permission.[31] Given that MSCHF did not make copies of the print, but rather cut up the version they bought, this seems to fit under the first sale doctrine.

Hirst did not bring legal action against MSCHF. Perhaps the statutory damages—ranging from $750 to $30,000 per work and up to $150,000 for willful violations—are not that enticing for a very commercially successful artist.[32] Furthermore, Hirst is known for unconventional boundary-pushing and may approve of MSCHF’s antics or find them to be in line with his own philosophy, even if he did not give express permission for the group to cut up and re-sell pieces of his print.[33]

“Satan Shoes”

MSCHF’s drop of their “Satan Shoes” in March 2021 caused quite a stir, particularly among intellectual property practitioners. The altered Nike Air Max 97s, made in collaboration with the rapper and singer Lil’ Nas X, were re-designed to include the following features: an upside down cross on the pull tab on the tongue, a pentagram attached to the laces, “Luke 10:18” printed on the side, the number edition for the pair (e.g. [#]/666), another pentagram printed inside the shoe, and a drop of blood mixed with red ink injected into the midsole. Crucially, the “Nike Swoosh” remains visible on each pair. 666 editions of the shoes were made and 665 were

purchased, for $1,018 each, within minutes (the last pair was kept by MSCHF for a giveaway).

Statement from MSCHF, dated April 1, 2021. Source.

While Nike sued over the “Satan Shoes,” they did not take action when MSCHF created a very similar product, the “Jesus Shoe” in 2019.[34] The “Jesus Shoes,” also altered Nike Air Max 97s, include the incorporation of frankincense wool, a cross on the laces, and injection of holy water from the Jordan River. MSCHF, in their statement page for satan.shoes, says “Who is Nike to censor one but not the other?”[35] Nike’s reasoning includes that the “Jesus Shoe” had fewer alterations, less sneakers were made, and that the Christian message did not engender the same blowback from consumers that the “Satan Shoes” did.[36]

Nike did not give its permission for their trademark to be used and was not connected with the project, but alleged that there was confusion in the marketplace as to the source of the “Satan Shoes.”[37] Nike sued in federal court on March 29, 2021 claiming trademark infringement and dilution, and sought a temporary restraining order, a permanent injunction, and damages.[38] Nike bolstered its argument that MSCHF’s use of their trademarks confused consumers by including multiple social media screenshots showing actual confusion as to whether Nike approved of this product.[39]

Though this case quickly settled in early April 2021, MSCHF did have a few key defenses at its disposal. One is the first sale doctrine, which, under trademark law, allows the production and sale of refurbished and enhanced goods as long as the refurbished goods are clearly marked as such.[40] However, Nike countered that the sneakers were materially altered in such a way that they were essentially new and unauthorized products, and thus, not protectable by the first sale doctrine.[41]

The other possible defense is expressive fair use, which permits unauthorized use of a trademark in an artistic or expressive work, if the mark is artistically relevant to the work and does not explicitly mislead consumers as to the source.[42] Nike argued that MSCHF used more of their trademark than was necessary for their purpose and that selling hundreds of sneakers is not akin to a trademark’s appearance in a satirical illustration or in a single painting.[43]

Conclusion

While the creatives at MSCHF continue to move forward and to push the boundaries of interventions, future disputes between them and those at the butt of their jokes are likely. However, there seem to be a few options for how these disputes get resolved. Negotiations and mediation seem like a good avenue as it keeps cost low and can be more efficient than court proceedings. Furthermore, the conversations would be confidential, which may be ideal for a collective that seeks to keep its operations somewhat undercover. Some, like Nike, may still opt to file a lawsuit and then leverage that into the negotiation process.

There is also the question of whether it is worth engaging with MSCHF legally. Even though MSCHF has money coming in from investors, they are still a small startup, not a huge company. Finally, bigger companies, and artists, may consider the optics of suing a creative collective that is poking fun at them or a larger industry practice. It might just prove MSCHF’s point if it looks like they cannot take a joke. When the next drop is always shrouded in mystery, who MSCHF might face next, across the negotiation table, or in court, remains unpredictable.

Endnotes:

- Sanam Yar, The Store of MSCHF, a Very Modern . . . Business?, N.Y. Times (updated Mar. 30, 2021). ↑

- Although MSCHF has raised $11.5 million in investments since fall 2019. See Yar, supra note 1. ↑

- See MSCHF, (@mschf), Twitter; MSCHF, (@mschf), Instagram. MSCHF’s Twitter and Instagram accounts both proclaim “DO NOT FOLLOW US.” It appears that MSCHF used to send notifications about its drops via a random phone number, but now uses an app. See Yar, supra note 1. ↑

- Yar, supra note 1. ↑

- The disclaimer for the auction lot stated: “As a buyer you recognize that this work represents a potential security hazard. By submitting a bid you agree and acknowledge that you’re purchasing this work as a piece of art for academic reasons, and have no intention of disseminating malware.” Taylor Dafoe, A Laptop Infected With Six of the World’s Most Dangerous Computer Viruses Is Up for Auction. The Bid Is Now More Than $1.2 Million, Artnet (May 22, 2019). ↑

- See Curtis Silver, The Blue Donkey Subverts Corporate Political Ideologies By Laundering Perks, Forbes (Nov. 12, 2019, 10:14 AM). MSCHF’s disclaimer read: “MSCHF might be covering its ass as best it can here, but it’s doubtful that Grubhub/Seamless will let this stand for very long.” Id. As MSCHF predicted, Grubhub/Seamless quickly shut down access to The Blue Donkey. MSCHF, The Blue Donkey (last visited May 6, 2021). ↑

- By “restricted” I mean the listings on MSCHF’s website that do not have a title (i.e. indicated as “XXXXX”). When you hover your mouse over a restricted listing, it indicates “RESTRICTED LVL 2 – GET ACCESS” and the accompanying hyperlink directs you to the Apple App store to download the MSCHF app. ↑

- MSCHF is also auctioning the remnants of the print, sans spots—the current bid as of this writing is $261,400. ↑

- See The Fashion Law, One of Damien Hirst’s Famed Sport Painting Prints Was Separated into 88 Spots, Which Were Then Sold Individually (Apr. 30, 2020). ↑

- Artsy, Damien Hirst (last visited May 10, 2021). ↑

- See 17 U.S.C. § 104 (2018). ↑

- U.S. Copyright Office Compendium: Chapter 2000, Foreign Works Eligibility and GATT Registration (last updated Jan. 28, 2021) (though registration of a foreign work is required in order to seek statutory fees or attorney’s fees). ↑

- See Michael S. Denniston, International Copyright Protection: How Does It Work?, Bradley (Mar. 28, 2012). ↑

- See 17 U.S.C. § 106(A) (2018). ↑

- 17 U.S.C. § 106(A)(3)(A). ↑

- See 17 U.S.C. § 106(A)(2). ↑

- See 17 U.S.C. § 106(A)(3)(B). ↑

- See Henry Lydiate, Moral Rights: A Suitable Case for Treatment?, Art Quest (2013). ↑

- See id.; Design & Artists Copyright Society (DACS), Frequently Asked Questions (last visited May 10, 2021). ↑

- See Lydiate, supra note 18. ↑

- See id.; Library of Congress, Copyright Office, Waiver of Moral Rights in Visual Artworks (Oct. 24, 1996); ↑

- 17 U.S.C. § 201(a) (2018); 17 U.S.C. § 106 (2018). ↑

- 17 U.S.C. § 101 “derivative” (2018). ↑

- See U.S. Copyright Office Circular 14: Copyright in Derivative Works and Compilations (2020). ↑

- 17 U.S.C. § 107 (2018). ↑

- Marano v. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, No. 20-3104 (2d Cir. April 2, 2021); Andy Warhol Found. For The Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, No. 1:17-cv-02532 (S.D.N.Y. July 1, 2019); Marano v. Metropolitan Museum of Art, No. 19-cv-8606, 2020 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 122515 (S.D.N.Y. July 13, 2020). ↑

- See The Fashion Law, supra note 9. ↑

- See Adrian Searle, Full circle: the endless attraction of Damien Hirst’s spot paintings, The Guardian (Jan. 11, 2012); see also, The Copyright Alliance, Why is Parody Considered Fair Use But Satire Isn’t (last visited May 6, 2021). ↑

- However, arguments opposing fair use may cite the fact that MSCHF sold the spots and was not merely using the piece for educational or research purposes. Additionally, MSCHF used the entire work to make this statement, not just a portion of it. ↑

- 17 U.S.C. 106(A) (“Subject to section 107. . .); see The Fashion Law, supra note 9; Cathay Smith, Creative Destruction: Copyright’s Fair Use Doctrine and the Moral Right of Integrity, 47 Pepp. L. Rev. 601, 601 (2020) (“there have been no decisions in the United States interpreting how the [fair use] doctrine might apply to a moral right of integrity claim”); Amelia Brankov, Brooklyn Collective Buys Damien Hirst “Spot” Work, And Then Cuts Out And Sells the 88 Spots At A Profit!, Frankfurt, Kurnit, Klein & Selz PC (May 1, 2020). ↑

- 17 U.S.C. § 109 (2018). ↑

- See The Fashion Law, supra note 9; 17 U.S.C. § 504 (2018). ↑

- See The Fashion Law, supra note 9. ↑

- See Maya Ernest, Why did Nike sue over the ‘Satan Shoes’ but not ‘Jesus Shoes’?, Input (Apr. 1, 2021, 2:32 PM). ↑

- MSCHF, Statement (Apr. 1, 2021). ↑

- See Davis & Tindell, supra note 41. ↑

- See Memorandum of Law in Support of Its Motion For a Temporary Restraining Order & Preliminary Injunction at 1-2, Nike, Inc. v. MSCHF Product Studio, Inc., No: 1:21-cv-01679 (E.D.N.Y. Mar. 30, 2021). ↑

- Id. at i. ↑

- Id. at 13-15. Nike included screenshots from social media as evidence of actual confusion, including the following quotes from people on Twitter: “‘Nike did not design or release these shoes and we do not endorse them.’ But you did give Permission. . .You. Can Only distance yourself so far. Everybody see that big ass Swoosh” and “All I’ve been seeing is bad feedback from these. Who at your company approved this? I literally want to know who thought this was a good idea. Literally makes me want to stop buying your brand. . .” Id. at 15-16. ↑

- See Champion Spark Plug Co. v. Sanders, 331 U.S. 125, 130 (1947). ↑

- Nadya Davis & Amy Tindell, Ph.D, Satan Shoes: Trademark Blasphemy or Free Speech?, IP watchDog (Apr. 13, 2021). ↑

- See Gordon v. Drape Creative, Inc., 909 F. 3d 257, 261 (9th Cir. 2018). In contrast to the four-factor test for copyright fair use, expressive fair use under trademark law has three requirements: defendant is using the mark in an artistic or expressive work; the mark being used is artistically relevant to the work’s expression; and defendant’s use of the mark does not explicitly mislead consumers as to the source or content of the work. See id. ↑

- See Davis & Tindell, supra note 41. ↑

About the Author: Laura Michiko Kaiser is a 2021 graduate of The George Washington University Law School and former legal intern at the Center for Art Law. Prior to law school, she worked as a paralegal in New York City. Laura earned her B.A. in Comparative Literature from New York University and completed course work in studio art, film, international literature, and cultural heritage. She is passionate about the art law field and hopes to be an attorney and advocate for artists and designers.

Disclaimed: This article is intended for educational use only. Opinions expressed herein are those of the Author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Center for Art Law.

Disclaimer: This article is for educational purposes only and is not meant to provide legal advice. Readers should not construe or rely on any comment or statement in this article as legal advice. For legal advice, readers should seek a consultation with an attorney.

You must be logged in to post a comment.