Legacy Over Licensing: How Artist Estates and Museums Are Redefining Control in the Digital Age

February 19, 2026

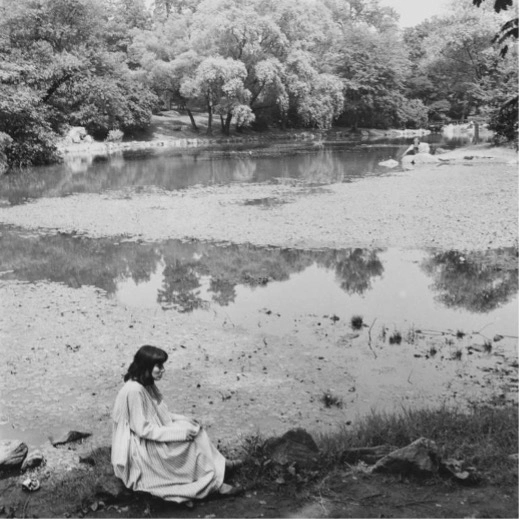

Robert Rauschenberg, Susan—Central Park N.Y.C. (II) (1951)

By Josie Goettel

When an artist passes, their estate is tasked with two seemingly conflicting tasks: to protect an artist’s work by exercising exclusive rights over them, and to disseminate their artwork to the public to establish a lasting legacy and placement in the art world. This dilemma runs parallel to another issue an estate faces when managing a body of art: should they prioritize revenue or improve public access to art? In recent trends, the answer seems to be the latter.[1]

Since earnest efforts started in the late 2000s and early 2010s, many art estates, foundations, and museums have moved away from traditional, restrictive image licensing and have moved toward open-access models for scholarly use, albeit at a revenue loss.[2] The Robert Rauschenberg Foundation (RRF) serves as a key example of the movement to increase public access to art by loosening fair use policies.[3] RFF’s decision to ease copyright restrictions for non-profit uses establishes a new, philanthropy-driven model for estate management, prioritizing the artist’s intellectual legacy and public engagement over short-term revenue generation.[4]

The Traditional and Digital Landscape

Traditional Model and its Costs

Historically, museums, artist foundations, and estates have treated image licensing of works by an artist as a significant source of revenue, often managed via third-party licensing agents, charging fees to publishers, educators and others to use images of works in print or online.[5] The logic was that such licensing income supports the archive, catalogues raisonnés, conservation efforts, residencies and other philanthropic operations of the foundation.[6] However, this model also carried significant costs for scholarship: high fees, slow approval processes, administrative burdens, and sometimes opaque terms or rights-holding.³ For many scholars and educators the prohibitive cost and delays of obtaining rights meant that images either went unused or substituted by lower-quality or unauthorized alternatives, thereby limiting engagement, complicating teaching, and inhibiting critical visual scholarship.[7]

Moreover, the licensing model can create a gatekeeping effect: the foundation holds the keys, and commercial as well as non-commercial users must negotiate, pay, and wait.[8] For the estate, this maintains control but also potentially limits the dissemination of the artist’s work and the conversation around it.[9]

Pressure to Digitize

The rise of digital archives, online scholarship, open‐access practices, and social media has altered the landscape of image-use.[10] Many users now expect high-quality digital copies, rapid access, and fewer rights-barriers.[11] At the same time, unauthorized, low-quality images proliferated across the web and social media—often lacking correct attribution, provenance or captioning.[12] The result has been a vacuum in which the estate or foundation’s officially licensed images risk being overshadowed by uncontrolled representations, mis-attributed works, or general confusion about the artist’s oeuvre.[13]

In this context, the traditional restrictive licensing model begins to look counter-productive to the maintenance and enhancement of an artist’s legacy; by denying access, the estate may inadvertently push users toward unofficial sources, or inhibit the kind of engagement that leads to richer scholarship, exhibitions and public interest.[14] As the RRF observed, “the fear of violating copyright restrictions resulted in … two unique challenges”— scholars often limited themselves to freely available images, or digital and social media usage was inhibited.[15]

The digital movement thus creates a dual pressure: museums and estates must continue to fund their operations, but also must embrace access and distribution if they want the artist’s work to remain vital.[16] That sets the stage for the shift we now observe.

Case Study: The Rauschenberg Foundation’s New Standard

The Policy and its Rationale

In February 2016, eight years after the artist’s passing, the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation announced a “pioneering Fair Use Image Policy” — described as the first such policy adopted by an artist-endowed foundation — that would make images of Rauschenberg’s artworks “more accessible to museums, scholars, artists, and the public.”[17] The foundation explained that prior to 2015 it had, like many others, safeguarded image use through licensing agents; over time it observed that this model was inhibiting scholarship, digital distribution and social-media sharing.[18]

Specifically, the RRF noted two key challenges: First, the “prohibitive costs associated with rights and licensing” meant many scholars or professors limited their usage to freely-available images, which in turn influences how art history is written and taught.[19] Second, complexities around online use and social media—where licensing for especially digital or derivative use remains fraught—meant that many institutions limited what they posted, leaving a vacuum of official, high-quality, correctly captioned images, which led to mis-attribution and proliferation of incorrect information.[20]

In response, the foundation piloted licenses in 2015 to select museums (including the Art Institute of Chicago, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA), the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Tate Modern.[21] Then, it expanded the Fair Use policy to the public at large.[22]

The foundation’s rationale is clear: For non-profit and scholarly uses, the value of widespread dissemination, accurate images and increased engagement outweighs the licensing income lost.[23] As one foundation executive put it: “We are pleased to announce … a new Fair Use policy … to make images of Rauschenberg’s artwork more accessible…”[24]

Measurable Impact

According to the article in The Art Newspaper, the adoption of the policy resulted in a “profound bump” in usage and engagement.[25] The CEO of the RRF, Christy MacLear, stated that “the benefits outweigh the income we lost.”[26] For example, she noted that approval for the use of Rauschenberg imagery in the work of the U.S. artist Rachel Harrison was secured in a single meeting — a demonstration of how streamlined the process now can be.[27]

From a legacy perspective, this increased visibility promotes more exhibitions, citations, scholarship, teaching and public awareness of Rauschenberg’s work.[28] The proliferation of high‐quality, correctly attributed images enhances the brand of the artist and his foundation, aligning with Rauschenberg’s own collaborative, interdisciplinary and accessible ethos.[29] It also fosters academic study, social-media circulation, and digital archival practices, ensuring the works remain present and discussed rather than fading into the margins of restrictive rights-holding.[30]

Financial Strategy

Naturally, loosening licensing for non-profit/scholarly use means sacrificing some revenue.[31] However, the RRF was financially positioned to absorb that sacrifice.[32] In the same article, it is noted that for-profit users still need permission and pay fees; the income from those licenses goes toward the foundation’s philanthropic work, such as around 100 artist residencies a year at Captiva (the artist’s former home and studio in Florida) and a planned catalogue raisonné.[33] The combination of the foundation’s endowment, other revenue streams (including sales of non-Rauschenberg works in his collection and estate sales) along with philanthropic programming give it enough flexibility to prioritize legacy over licensing income.[34]

Thus, RRF’s model can be read as a strategic decision: sacrifice a portion of licensing revenue (in the non-profit/scholarly domain) in exchange for greater long-term legacy value, academic engagement and brand enhancement. In effect, the foundation redefines success not purely in financial terms but in cultural and scholarly impact.[35]

The Shift as a New Model: The Mike Kelley Foundation and Critique

The Mike Kelley Foundation’s Consideration

The trend to loosen restrictions had ripple effects in the art foundation and museum sphere.[36] Immediately following the Rauschenberg announcement, the Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts was “considering free reuse for non-profits.”[37] John Welchman, chair of the Kelley board and a professor at the University of California, San Diego, noted that he was open to the idea of “easing restrictions.”[38] This idea has since been formalized and implemented.[39]

This shows that estates beyond Rauschenberg are weighing the public benefit of open access, or licensing revenue. The Kelley Foundation is particularly significant because Mike Kelley’s work is complex, critically rich and benefits from broad scholarly engagement.[40] An open access approach could stimulate new scholarship, reinterpretations and public interest in the estate.[41]

The Limits and Critique

However, the model is not without critique. Rights management organisations such as the World Intellectual Property Organization caution that distinguishing “non-profit” from “for-profit” uses is often blurry;[42] Museum and educational uses may still involve commercial benefit (catalogues, admission ticket revenue, donor attraction).[43] Marc Waugh, head of research at DACS, noted that although artists are told wider publication of their work is “good for their profile,” they should still receive remuneration.[44]

Moreover, the replicability of the RRF model across smaller or less-endowed foundations is questionable.[45] Not every artist estate has a strong market, substantial endowment, or alternate revenue to absorb licensing income loss.[46] For smaller‐scale estates or artists with less commercial cachet, the licensing income may be essential for operational funding (archives, catalogues, conservation).[47] Without that income, loosening rights could jeopardise the estate’s capacity to function.[48]

There is also the risk of unintended consequences, as increased access can lead to oversaturation or loss of exclusivity, which might degrade perceived market value.[49] The estate must balance access with market dynamics, brand protection and appropriate use.[50] Some might argue that image licensing is not simply about revenue but about stewardship and quality control—ensuring images are accurate, well-captioned, and used in appropriate contexts.[51] The shift toward open access may undermine that control.[52]

Thus, while the RRF case is compelling, it may not be a one‐size‐fits‐all model.[53] Estates must assess their particular circumstances (market strength, endowment, philanthropic mission, archive scale) before adopting a similar approach.[54]

Conclusion

The case of the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation reveals that an artist-estate can reframe its role from licensing gatekeeper to proactive facilitator of legacy, scholarship and public engagement. By loosening fair-use and image-licensing restrictions for non-profit and scholarly use, the Foundation accepted a revenue sacrifice in favour of wider access, visibility, and alignment with the artist’s disposition.

Looking forward, the Mike Kelley Foundation’s following and beyond suggests this shift is not simply an isolated case but may herald a new best-practice for art foundations navigating the digital public sphere. As digital media, social platforms and open-access scholarship continue to accelerate, estates that cling to restrictive models risk losing relevance, control and scholarly engagement.

Ultimately, the success of the RRF model compels foundations to redefine the metrics of success: not just licensing income, but cultural impact, academic engagement, correct attribution, image quality, public awareness and long-term legacy. The balance between revenue and access tilts in favour of access—perhaps not in every case equally, but increasingly in the arena of major artist foundations.

About the Author

Josie Goettel (Center for Art Law Fall 2025 Intern) is a 2L at University of California College of the Law, San Francisco. There, she is the President of the Law and Intellectual Property Association and a staff editor on the Communications and Entertainment Law Journal. After law school, she hopes to practice in the intellectual property or art law field.

Suggested Readings

- Kenneth D. Crews, Museum Policies and Art Images: Conflicting Objectives and Copyright Overreaching (2015)

- Phil Malone, Berkman Ctr. for Internet & Soc’y, An Evaluation of Private Foundation Copyright Licensing Policies, Practices and Opportunities (2009).

- Rachel Hoster, Art Museums and the Public Domain: A Movement Towards Open Access Collections, (2020).

Select References

- Javier Pes, Mike Kelley Foundation Could Follow Rauschenberg’s Lead Over Image Copyright, The Art Newspaper (Sept. 15, 2016), https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2016/09/15/mike-kelley-foundation-could-follow-rauschenbergs-lead-over-image-copyright. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Robert Rauschenberg Found., Foundation Announces Pioneering Fair Use Image Policy, (Feb. 29, 2016), https://www.rauschenbergfoundation.org/news/foundation-announces-pioneering-fair-use-image-policy. ↑

- Carolina A. Miranda, Why the Rauschenberg Foundation’s easing of copyright restrictions is good for art and journalism, L.A. Times (Mar. 4, 2016), https://www.latimes.com/entertainment/arts/miranda/la-et-cam-robert-rauschenberg-foundation-copyright-20160304-column.html. ↑

- Brian L. Frye, Image Reproduction Rights in a Nutshell for Art Historians, 62 IDEA 175, 178, (2022); See generally Code of Best Practices in Fair Use for the Visual Arts, Center for Media and Social https://cmsimpact.org/code/fair-use-for-the-visual-arts/ [https://perma.cc/DF8P-XFR2] (last visited Nov 18, 2025). ↑

- Foundation Announces Pioneering Fair Use Image Policy, supra note 1. See genrally Effie Kapsalis, The Impact of Open Access on Galleries, Libraries, Archives, and Museums (Smithsonian Emerging Leaders Dev. Prog., Apr. 27, 2016). ↑

- Rosemary Chandler, Note, Putting Fair Use on Display: Ending the Permissions Culture in the Museum Community, 15 Duke L. & Tech. Rev. 61, 74 (2017). ↑

- Id. ↑

- Phil Malone, Berkman Ctr. for Internet & Soc’y, An Evaluation of Private Foundation Copyright Licensing Policies, Practices and Opportunities, 26 (2009). ↑

- Rachel Hoster, Art Museums and the Public Domain: A Movement Towards Open Access Collections, 47 VRA Bull., no. 2, Dec. 12, 2020, art. 4. ↑

- Kapalsis, supra note 4 at 17. ↑

- Grischka Petri, The Public Domain vs. the Museum: The Limits of Copyright and Reproductions of Two-Dimensional Works of Art, 12 J. Conservation & Museum Stud., art. 8, 1 2014. https://doi.org/10.5334/jcms.1021217; Kristin Kelly, Images of Works of Art in Museum Collections: The Experience of Open Access, 27-28 (Council on Libr. & Info. Res. ed., 2013). ↑

- Id. ↑

- Petri, supra note 12 art. 8 at 1. ↑

- Robert Rauschenberg Found., supra note 3. ↑

- Kelly, supra note 12 at 24. ↑

- Robert Rauschenberg Found., supra note 3. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Kelly, supra note 12 at 24. ↑

- Robert Rauschenberg Found., supra note 3. ↑

- Pes, supra note 1. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Malone, supra note 9 At 29. ↑

- Robert Rauschenberg Found., supra note 3. ↑

- Miranda, supra note 4. ↑

- Kelly, supra note 12 at 3. ↑

- Pes, supra note 1. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Robert Rauschenberg Found., supra note 3. ↑

- Pes, supra note 1; Kathryn Goldman, Museums that Give Away Open Access Images of Public Domain Work, Creative Law Ctr. (Feb. 15, 2020), https://creativelawcenter.com/museums-open-access-images/. ↑

- Pes, supra note 1. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Pes, supra note 1; Terms & Conditions, Mike Kelley Found. for the Arts, https://mikekelleyfoundation.org/terms-and-conditions (last visited Nov. 19, 2025). ↑

- Matt Copson & Jean-Marie Gallais, Mike Kelley, CURA. (2023–24), https://curamagazine.com/digital/mike-kelley/. ↑

- Kelly, supra note 12 at 24-25. ↑

- Raquel Xalabarder, Study on Copyright Limitations and Exceptions for Educational Activities in North America, Europe, Caucasus, Central Asia and Israel 52 (World Intell. Prop. Org. Standing Comm. on Copyright & Related Rights, SCCR/19/8, 2009). ↑

- Id. ↑

- Pes, supra note 1. ↑

- Malone, supra note 9 at 48. ↑

- Artist Estates and Fiduciary Duties, Stropheus (Apr. 30, 2025), https://stropheus.com/art-law-updates/artist-estates/. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Kenneth D. Crews, Museum Policies and Art Images: Conflicting Objectives and Copyright Overreaching,22 Fordham Intell. Prop. Media & Ent. L.J. 795, 812 (2015). ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Malone, supra note 9 at 48. ↑

- Stropheus, supra note 46; Malone, supra note 9 at 48; Crews, supra note 50 at 812. ↑

Disclaimer: This article is for educational purposes only and is not meant to provide legal advice. Readers should not construe or rely on any comment or statement in this article as legal advice. For legal advice, readers should seek a consultation with an attorney.