WYWH: “Arte Liberata” – An Exhibition to Investigate the Italian Struggle to Protect the Country’s Cultural Heritage during World War II *

March 9, 2023

By Livia Solaro

From December 16, 2022 to April 10, 2023, the Scuderie del Quirinale in Rome is entirely dedicated to the exhibition “ARTE LIBERATA 1937-1947. Masterpieces saved from war,” a sui generis itinerary that guides visitors across the incredible adventure(s) of the men and women who strived to protect Italy’s cultural treasures during the most tragic decade of its history.

By showcasing a remarkable selection of masterpieces (visitors are greeted by the Discobolus Lancellotti and end their tour under the ecstatic gaze of Tiziano’s Danae), the exhibition offers a novel look into a chapter of World War II that is often reduced to the intervention, during the conflict’s final years, of the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives program (better known as Monuments Men). The goal behind “Arte Liberata” is to let visitors dive into the exploration of what happened at the national level prior and around the Monuments Men’s arrival to Sicily. To this end, a series of highly detailed exhibition panels (accompanied by some fascinating archival materials) provide information both in Italian and English. The final result is a well-rounded reconstruction of the challenges and choices that marked a decade, adding a new layer to an important chapter in the history of cultural property protection in times of war.

A different perspective

The peculiarity of the initiative is already evident from its title. When discussing Nazi looted artworks, it is not uncommon to read how they were recovered, for example, from the Altaussee salt mine or rescued from private collections, such as that amassed by Hermann Göring in his Carinhall estate; when successfully identified by the national delegations, they were then returned from the German collecting points to the countries they had been plundered from.[1] To define art as being liberata (liberated), however, is quite unusual and potentially confusing; after all, most of the pieces on display never fell under enemy control nor did they leave the national territory, thus requiring no “liberation.” The choice of words, however, needs to be read in connection to the concept of Liberazione, which indicates the end of the Nazi occupation of Italy and the simultaneous fall of the Fascist regime. Liberazione is, in turn, deeply intertwined with the ideals of the Resistenza, the relentless guerilla fight carried out by the partigiani after the 1943 Armistice officially turned the German allies into invaders. In this context, cultural property protection is presented as yet another front on the battle for freedom and its protagonists as heroes of their own account. By transcending the familiar boundaries of “restitution,” the meaning of this exhibition becomes heavily political, as the untold stories of museum directors, curators, and art historians are presented as a proper component of the fight for Liberazione.[2]

And yet, the risk of falling into a flat and nationalist glorification of the past remained a pretty big one, especially in light of the current Italian political climate (Scuderie del Quirinale is, like most museums in Italy, a public institution). Indeed, the Minister of Culture’s contribution to the exhibition’s catalogue heavily insists on the patriotic sense of pride and gratitude towards these unlikely heroes.[3] Thankfully, the universality of values and ideals behind the individuals’ efforts for the protection of cultural properties is strongly highlighted throughout the exhibition. Thus, albeit organized as a collection of stories, “Arte Liberata” ends up telling a much broader tale of war and culture, as a handful of intellectuals and public officials found themselves fighting a battle that was way bigger than any of them.

Regrettably, the exhibition does not make any mention of the separate, yet deeply correlated issue of those cultural properties that were taken by the Italian government, in force of the Fascist racist policies that, starting from 1935, were adopted against Jewish families; nor does it touch at any point upon the possible presence, within the Italian public collections, of artworks whose provenance might be unclear (or the lack of efforts, at the national level, to investigate in this regard). While clearly focused on a different aspect of the affair, this lack of consideration for “the other side of the coin” represents an evident flaw in an otherwise beautifully organized exhibition.

A presentation of stories through space and time

The ambitious goal of the exhibition to offer both an artistic and a didactic experience is effectively supported by an efficient organization of the materials along three narrative strands: one strand follows the forced or illegal exportations of protected artworks, one focuses on the moving and hiding of hundreds of thousands of cultural goods across the national territory, and a small conclusive part deals with the repatriation negotiations that took place after the end of the conflict. Each theme is addressed in a separate section, which avoids any overlap of contents and allows the exhibition to open and close with the most valuable pieces on display.

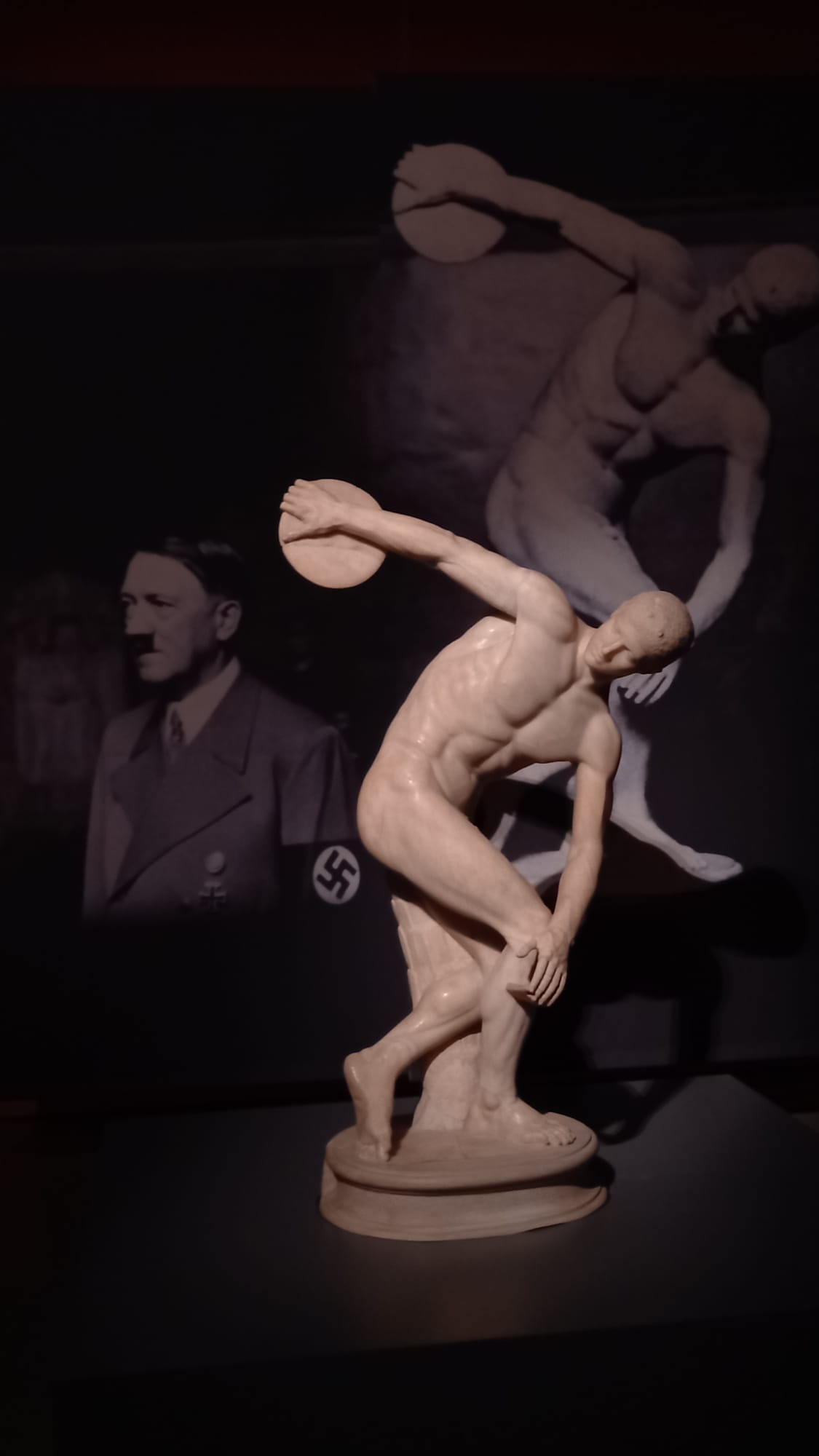

These three narratives also follow a chronological order: forced exportations – dealt with at the beginning of the exhibition – occurred at a time when the Nazi regime was still considered a valuable ally, and Fascist high officials intervened to facilitate (or outright impose) the sale of cultural goods that, according to the Italian cultural heritage law then in force, should not have left the Italian territory. Probably the most striking example of such a praxis is the sale of the Discobolus, which was requested in 1938 by Philipp von Hessen-Kassel on behalf of Hitler himself. Regardless of the restrictions imposed by the law, and the negative opinion of the Minister of Education Giuseppe Bottai himself, the marble statue – widely considered to be the best Roman copy of the long-lost bronze Discobolus of Myron – ended up in the Glyptothek München as a gift from the Führer to the German people.

Next to the statue, a short extract from the film “Olympia” by Leni Rifensthal provides the visitors with some background to Hitler’s fixation with this work of art (which prompted the involvement of the Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs Galeazzo Ciano to secure the positive conclusion of the sale). The prologue of the film, realized in celebration of the 1936 Berlin Olympic games, saw several statues of athletes – including the Discobolus – turn into as many sculptured humans in an evocative scene that had indelibly struck the imagination of the Führer. This is only one of the ample exceptions made during the Fascist years to the safeguards already in place at the time for “things of artistic, historical, archeological or ethnographic interest” (an even more stringent legislation was adopted in 1939).

The influence of the powerful Nazi ally bore a significant impact also on the private market, where several objects that should have never exited the country were sold to German art professionals and enthusiasts. The exhibition makes an example out of the “Ventura affair,” whereby sixteen works of art were sent by the antique dealer Eugenio Ventura to Göring, in exchange for various French masterpieces that had been previously looted from the private collections of some prominent Jewish families in occupied France. How the two sets of artworks entered and left the Italian soil was never clarified, with the Soprintendenza (the competent administrative authority) providing contradicting and incomplete information. The exchange also highlights the willingness, at least by a portion of the private sector, to overlook the 1942 London Declaration, which aimed at discouraging precisely these kinds of transactions.

National and regional efforts: the two sides of the protection of cultural heritage

As “Arte Liberata” focuses on the active fight against Nazi plunder and the measures taken to preserve artworks in the midst of the war, it is the second of its three main narratives that represents the true heart of the exhibition. From the second room onwards, the tale of the myriad of operations that took place before and during the war is told in great – and unprecedented – detail, starting with the national preparations that took place during the hectic nine months between the beginning of the conflict and Italy’s entry into war. Official decrees ordering nationwide surveys and inventories, signed by the Minister of Education Bottai, hang on the walls of the Scuderie (which, in turn, are covered by planks of raw wood to mimic the crates used to store the artworks).

Taking the operations carried out by the Spanish museums during the Spanish Civil War as a model of what not to do, Bottai envisioned a war preparation plan that would not require the artworks to leave the country. Photographs and videos from the historical archive Istituto Luce also offer powerful images of iconic monuments and cultural landmarks buried under bags of sand or disappearing under anonymous hard wooden structures. Walking across the rooms, visitors witness the arches of the Colosseum being filled up to prevent structural collapses, Trajan’s Column progressively wrapped in several protective layers, or Canova’s statue of Paolina Bonaparte hidden under a weirdly pyramidal cage. s World famous museums, such as Galleria Borghese in Rome or the Egyptian museum of Turin, were systematically emptied of their collections, an astonishing flow of artworks had to be directed towards a series of refuges identified by the local Soprintendenti and museums’ directors.

It is at this point that the historical events split into a collection of regional tales that are individually presented in different sections of the exhibition. Starting from the middle of the country, so to speak,[4] the first regional story to be covered is that of the Marche region, whose position and geography made it an ideal destination for the crates of art coming from all across Italy. Thanks to the significant loans from the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche, “Arte Liberata” hosts a great number of artworks that were moved to and across the region, in order to be stored within the thick walls of Renaissance fortifications like the Rocca di Sassocorvaro or historical buildings like the Palazzo dei Principi Falconieri in Carpegna.

This region’s vicissitudes are also particularly illustrative of the tragic practical consequences of the 1943 Italian Armistice, which unexpectedly overturned the previous power dynamics and local balances. All of a sudden, what had been considered to be the safest region in Italy was caught in between the two enemies’ lines; consequently, many of the refuges previously identified had to be evacuated once more, and new shelters had to be found either before the arrival of the Kunstschutz or to avoid the Nazi punitive expeditions. Similar situations arose across all of the Italian territory, with the additional complication that – with the country split in two – there no longer was a central administration coordinating the operations of safekeeping of cultural goods, leaving every man and woman for themselves.

The names and faces behind history: the individuals who stepped up

Next to the wool and silk tapestries, frescoes, marble and bronze busts, original Rossini’s scores, pottery and tondos, the Scuderie adds the names – and often the photographs – of those responsible for their salvage. Visitors are then presented with the stories of a handful of foresighted museum directors, such as Fernanda Wittgens, Noemi Gabrielli, and Jole Bovio Marconi, who moved their collections right before a military attack could destroy or damage them, or that of Pasquale Rotondi, the Soprindentente responsible for the fate of around 10,000 artworks (including several Caravaggios that had arrived from San Luigi dei Francesi and Santa Maria del Popolo in Rome and the San Marco treasure from Venice). Pietro Zampetti, from Modena, had only his bike to transport pieces from the Estense collection from one place to another, and Emilio Lavagnino managed to negotiate with the Vatican the reception of those artworks that could no longer remain on Italian soil. Lavagnino then helped carry them there himself, using his family car that ran on gasoline acquired on the black market.[5]

As visitors make their way through the exhibition, the list of names goes on, as does the tale of the adventurous (and often desperate) operations whose reality is restored through the incredible archival photographs of the artworks. The contrast is striking: whereas the artworks are now securely positioned onto solid pedestals, or hang behind a hyper-sensitive alarm system, the exhibition’s pictures show them almost forgotten in a corner of some museum closed off to the public or dangerously positioned on the edge of an open carriage of a cargo train. A sense of precarity lingers in each room of the Scuderie, perfectly captured by the details in the stories on the walls: the artworks had to be carried, depending on the region, on the back of donkeys, by bicycle, on Gondolas, or with small cars driven at night with the lights off.

After the war and beyond

After rooms of pasty wooden planks, black and white photographs, and artworks placed over rough blocks of pine, the final room of the exhibition greets the visitors with a red velvet curtain embracing Tiziano’s Danae, the final piece on display. The space of the Scuderie is seamlessly connected to the iconic photograph (reproduced next to the painting) of Rodolfo Siviero – the man considered responsible for many of the post-war restitutions to Italy.

The picture, which celebrates the return to Italy of the Danae (reportedly used by Göring as his personal headboard), also introduces the visitors to the last narrative thread of the exhibition: namely, the delicate process of negotiating the return of artworks subtracted at a time when Italy was still an ally of Nazi Germany and that were often “sold” and semi-lawfully exported rather than outright stolen. On top of that, the 1943 Armistice entailed an unconditional surrender, which, in itself, questioned the possibility of any such request on the part of the Italian delegation. Only an amendment to section 77 of the Peace Treaty with Italy, and subsequent extensive negotiations that culminated in a 1953 agreement between the Italian Prime Minister De Gasperi and German Chancellor Adenauer, ensured the return of numerous artworks that had left the country during the war.

While presented as an undiscussed protagonist of this phase, Siviero is also framed as a controversial and problematic character, considering his unwavering determination and sometimes questionable methods. In a way, Siviero’s picture also creates a trait d’union between “Arte Liberata” and the two major exhibitions that, in the aftermath of the war, were organized (with the help of Siviero) to celebrate what had been emphatically called “the return of Beauty” to Italy. It is by virtue of this connection that it is possible to further appreciate not only the evolution of the sensibility around the concept of restitution but also the emphasis put by this exhibition on the efforts and preparations to protect an invaluable cultural heritage at all costs.

Practical information

“ARTE LIBERATA 1937-1947. Masterpieces saved from war” is open from 16 December 2022 to 10 April 2023, and is curated by Luigi Gallo and Raffaella Morselli. The exhibition is organized by Scuderie del Quirinale in Rome (Via XXIV Maggio 16 – 00187 ROMA). A series of conferences will cover those aspects that could not be discussed within the exhibition itself (the full program is available on the website of the Scuderie, alongside the recordings of the conferences that already took place: https://www.scuderiequirinale.it/).

* The exhibition’s catalogue “ARTE LIBERATA Capolavori salvati dalla guerra 1937-1947” (ed. by Luigi Gallo and Raffaella Morselli, Electa 2023) was used as a valuable source while writing this article.

About the author:

Livia Solaro is a PhD candidate at Maastricht University (Netherlands), where she is involved in the teaching of Property law, Private international law and Art law; her research project focuses on the study of Nazi looted art litigation in the US, a topic on which she has recently published a book in Italy: “Il saccheggio nazista dell’arte europea: Uno Sguardo Comparatistico sul Contenzioso Transnazionale nei Restitution Cases” (Franco Angeli Edizioni, 2022), available in Open Access at https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/54283.

- For a complete historical account of the Nazi plunder of artworks, see Lynn H Nicholas, “The Rape of Europa: The Fate of Europe’s Treasures in the Third Reich and the Second World War” (Vintage Books) (1995). ↑

- As explained by Paolo Conti, an Italian journalist and the author of a short pamphlet that comes with the ticket and provides visitors with a short introduction to the exhibition. ↑

- Ed. by Luigi Gallo and Raffaella Morselli, “Arte Liberata, Capolavori salvati dalla guerra. 1937-1947” (Electa) (2023), p. 10. ↑

- Marche sits at the very centre of Italy, halfway between the North and the South, and it covers part of the Appennini, the mountain chain situated between the Eastern and Western coasts of Italy. ↑

- We then have Antonio Morassi and Orlando Grosso, who were active in the Liguria region (which was bombarded the day after Italy had entered the war), as well as Gino Fogolari, Vittorio Moschini and Rodolfo Pallucchini, who operated in Venice, where transportations were particularly problematic – due to the peculiarities of the city – and the risk of an attack was extremely high at all times. ↑

Disclaimer: This article is for educational purposes only and is not meant to provide legal advice. Readers should not construe or rely on any comment or statement in this article as legal advice. For legal advice, readers should seek a consultation with an attorney.

You must be logged in to post a comment.