Case Review Update: Thaler v. Perlmutter (2025)

June 20, 2025

By Shelby Jorgensen

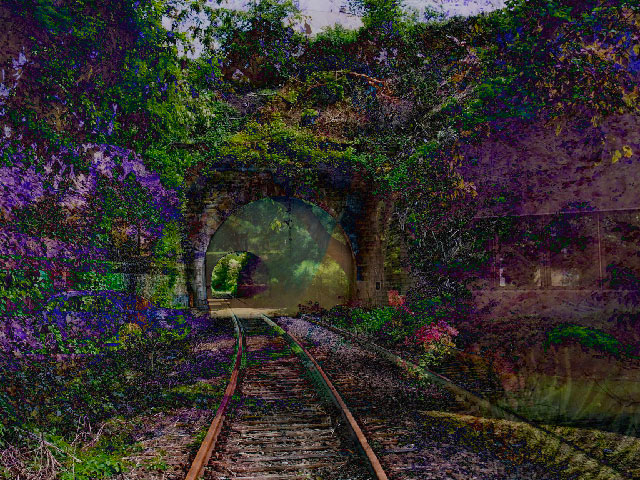

A Recent Entrance to Paradise is enjoying more than 15 minutes of attention. The Center has previously covered the District Court decision for this case back in 2023, which can be found here.

In March 2025, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit confirmed the District Court and Copyright Office’s denial of Thaler’s copyright application for “A Recent Entrance to Paradise.”[1] The on-going interest in AI- copyright related disputes and their potential long-term implications, warrants a closer look at this protracted legal battle between a computer scientist and the Copyright Office.

Facts and Background of the Case

According to Thaler’s petition, A Recent Entrance to Paradise is an image created by the “Creativity Machine,” a generative artificial intelligence developed by Thaler.[2] In 2018, Thaler filed a copyright application listing the Creativity Machine as the author, and asserted that the work was made for hire, with ownership vesting in him as the machine’s owner..[3] The Copyright Office denied the application twice.. The first denial, in August 2019, concluded that the work lacked “the human authorship necessary to support a copyright claim.”[4] Using Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co. v. Sarony, the Office stated that any claim for non-human authored work would be denied.[5]

Thaler requested reconsideration initially on the basis that restricting copyright claims to those with a human author infringes on constitutional rights.[6] He argued that copyright protections on works from AI would promote the development of creative focused AI, suggesting that automatic ownership of works made from such creative AI should go to the owner of the creative AI.[7] Thaler stated that current precedent is not binding on the specific issue of if AI-created works can be copyrighted, and suggested that the current acceptance of a corporation holding a copyright defeats the question of if a non-human can hold a copyright.[8]

In March 2020, the Copyright Office reaffirmed its denial.[9] It expounded on their previous decision stating they “will not register works produced by a machine or mere mechanical process that operates randomly or automatically without sufficient creative input or intervention from a human author.”[10] Thaler requested an additional reconsideration in May 2020.[11] The Copyright Office once again affirmed their original decision reiterating prior Supreme Court precedent regarding the requirement for human authorship and mentioning the multiple federal agency reports that follow the same standard.[12] The Copyright Office went on to state that the work made for hire argument is invalid because an AI cannot be a party to a contract and therefore cannot be hired to create.[13]

As mentioned in the Center’s previous article by Atreya Mathur, the District Court focused more narrowly than Thaler would have preferred, solely answering the question of if non-human creation can be protected with copyright.[14] The court discussed the historical context of copyright protections including the Copyright Clause, previous statutes, and precedent.[15] The court stated that the human authorship requirement “rests on centuries of settled understanding,” and found that in no prior case law did a court recognize copyright for a non-human author.[16] Although the court mentioned the complications that might arise due to human interaction with AI, it saw the present case as fairly cut and dry due to Thaler’s own admission that the work was created by the machine.[17] For the court, this lack of human involvement and the settled case law regarding this requirement, meant that the Copyright Office was correct in its denial of Thaler’s claim.[18]

Post the District Court’s decision Thaler appealed to the DC circuit court.

Issues

The question for the court remained the same: can a non-human authored work obtain copyright protection under the Copyright Act of 1976.[19]

Analysis

Like the District Court, the Circuit Court passed over the question of constitutionality.[20]

The Circuit Court began its analysis by examining the relevant provisions of the Copyright Act of 1976.[21] It specifically focused on the immediate vesting of copyright ownership, the protection term length of the life of an author plus 70 years, and the work-made-for-hire sections.[22] The court also gave a brief overview on the process outlined for obtaining copyright protections including the self-published regulations the Copyright Office follows which contains the human authorship requirement.[23]

Using textual interpretation the court focused on the use of the word “author” within the Copyright Act of 1976.[24] The court ran through a multitude of provisions within the Copyright Act, showing how interpreting the word “author” to include non-human sources would cause the text to be incongruous.[25] The court discussed multiple examples stemming from the Copyright Act’s text including that the author must be able to hold a possessory interest in order for the ownership interest to properly vest, have a lifespan for the copyright to have the proper term limits, have the legal capability to sign a document, and be capable of forming intent.[26] The court also mentioned how the Copyright Act defines and refers to machines in comparison to the word author, showcasing how interpreting author to include a machine would cause issues with the statute as a whole.[27]

The court also discussed the Copyright Office’s history of interpretation regarding the definition of authorship.[28] The court believed that the report published by the National Commission on New Technological Uses of Copyright Works (“CONTU”) reflected the intentions of lawmakers around the time regardless of the fact that the report was published two years after the Copyright Act.[29] The report by CONTU specifically stated that there is “no reasonable basis for considering that a computer in any way contributes authorship to a work produced through its use.”[30] The report came to the conclusion that a computer could not act as an author, but only as a tool to help a human create.[31]

In direct response to Thaler’s argument regarding work-made-for-hire, the court hinged its argument on the word “considered,” stating that the inclusion of this word means that a corporation or other entity who hired someone to create a work is not actually the author.[32] Therefore, the title of author is reserved for the human that actually created the work.[33]

Regarding Thaler’s assertion that the human authorship requirement would hamper works made with AI, the court limits its decision to works where the sole author is AI, declining to extend its logic over AI-assisted works.[34] The court mentioned previous copyright applications for AI-assisted works including Zarya of the Dawn, which was ultimately restricted to exclude an artwork created by AI, as a more complex question to be reserved for a different circumstance.[35] The court had a moment of levity when discussing economic incentives, explaining that AI’s creative power should not be impacted by its inability to act as a sole author because current AI technology has not yet reached the technical acuity to respond to economic implications unlike that of science fiction depictions including Star Trek’s Data.[36]

Additionally, the court reasoned that Congress’s lack of action to change the human author requirement shows an implicit acceptance of the judicial and agency construction.[37] Finally the court acknowledged ongoing conversations on how copyright law should shift to react to technology developments, but declined to make such a determination itself, seeing such a move as a job reserved for Congress.[38]

On May 2, 2025 Thaler petitioned for a panel rehearing.[39] This has been denied.[40]

Thaler has been erstwhile prolific in his pursuit to obtain IP protections with AI being listed as the creator. In 2023 the Supreme Court denied his writ of certiorari regarding an appeal from his US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit case.[41] Thaler had listed a different AI he created called DABUS as the inventor for an emergency light and a drink holder.[42] The Patent Office rejected his application with the Circuit court affirming this decision on the basis that an inventor must be human.[43]

Conclusion

This case addresses a narrow but significant question: whether AI can be considered the sole author of a work eligible for copyright protection. It also skirts the edge of the more complex conversation regarding how much direct human involvement would qualify an AI-assisted work for a copyright claim. The court is obviously open to further arguments and understands the implications of how generative AI will be defined,[44] but is also reluctant to make sweeping decisions it sees as reserved for the Legislative Branch.

Although understandable that the Appeals Court declined to comment on Thaler’s assertion that an AI work’s copyright should be held by the owner of the AI, this belief could be problematic. Especially in the case of something like Zarya of the Dawn, which was created using Midjourney, an AI that was not owned or created by the copyright applicant, Kashtanova.[45] Kashtanova, unlike Thaler, was not involved in the creation of Midjourney.[46] This could introduce an additional question over if the original creator of the AI has a stronger claim compared to the user of the AI.

Suggested Readings

- Developments in the Law: Chapter Two Artificial Intelligence and the Creative Double Bind, 138 Harv. L. Rev. 1585 (2025).

- Zach Winn, If art is how we express our humanity, where does AI fit in?, MIT News, June 15, 2023.

- Ted Chiang, Why A.I. Isn’t Going to Make Art, The New Yorker, Aug. 31, 2024.

- Nadia Banteka, Artificially Intelligent Persons, 58 HOUS. L. REV. 537, 593 (2021)

- Comments of the Motion Picture Association, Inc. Docket No. USCO 2023-6 (Oct. 30, 2023)

About the Author

Shelby Jorgensen is a rising 2L at the University of Wisconsin Law School, working as a Summer 2025 Legal Intern for the Center for Art Law. A 22’ graduate from the University of Notre Dame with a dual degree in marketing and studio art, Shelby hopes to combine her love for art with her interest in the law to work as an intellectual property attorney. She can be contacted for questions or comments at sjorgensen4@wisc.edu.

Sources:

- Thaler v. Perlmutter. 130 F.4th 1039, 1039-41 (D.C. Cir. 2025). ↑

- Id. ↑

- Copyright Review Board, Second Request for Reconsideration for Refusal to Register A Recent Entrance to Paradise (Correspondence ID 1-3ZPC6C3; SR # 1-7100387071), available at https://www.copyright.gov/rulings-filings/review-board/docs/a-recent-entrance-to-paradise.pdf ↑

- Defendant’s Exhibit D at 1, Thaler v. Perlmutter, 687 F. Supp. 3d 140 (D.D.C. 2023) (1:22-cv-01564). Available at https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.dcd.243956/gov.uscourts.dcd.243956.13.4.pdf ↑

- Id. ↑

- Defendant’s Exhibit E at 1, Thaler v. Perlmutter, 687 F. Supp. 3d 140 (D.D.C. 2023) (1:22-cv-01564). Available at https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.dcd.243956/gov.uscourts.dcd.243956.13.5.pdf ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. at 6-7. ↑

- Defendant’s Exhibit F at 1, Thaler v. Perlmutter, 687 F. Supp. 3d 140 (D.D.C. 2023) (1:22-cv-01564). Available at https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.dcd.243956/gov.uscourts.dcd.243956.13.6.pdf ↑

- Id. ↑

- Defendant’s Exhibit G at 1, Thaler v. Perlmutter, 687 F. Supp. 3d 140 (D.D.C. 2023) (1:22-cv-01564). Available at https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.dcd.243956/gov.uscourts.dcd.243956.13.7.pdf. ↑

- Copyright Review Board, Second Request for Reconsideration for Refusal to Register A Recent Entrance to Paradise (Correspondence ID 1-3ZPC6C3; SR # 1-7100387071), available at https://www.copyright.gov/rulings-filings/review-board/docs/a-recent-entrance-to-paradise.pdf ↑

- Id. ↑

- Thaler v. Perlmutter, 687 F. Supp. 3d 140, 145-46. (2023). ↑

- Id. at 147-50. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Thaler v. Perlmutter, 130 F.4th 1039, 1041 (D.C. Cir. 2025). ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. at 1042. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. at 1042-43. ↑

- Id. at 1045. ↑

- Id. at 1045-46. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. at 1047. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. (quoting CONTU, Final Report at 44 (1978), https://perma.cc/7S8T-TAB5.). ↑

- Id. at 1048. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. at 1049. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. Copyright Review Board, Zarya of the Dawn (Registration # VAu001480196) (Correspondence ID 1-5GB561K), available at file:///Users/shelbyjorgensen/Desktop/CfAL/zarya-of-the-dawn.pdf. ↑

- Thaler, 130 F.4th at 1050. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. at 1050-51. ↑

- Thaler v. Perlmutter, No. 23-5233, 2025 U.S. App. LEXIS 11500 (D.C. Cir. May 12, 2025). ↑

- Id. ↑

- Blake Brittain, US Supreme Court rejects computer scientist’s lawsuit over AI-generated inventions, Reuters (Apr. 24, 2023) https://www.reuters.com/legal/us-supreme-court-rejects-computer-scientists-lawsuit-over-ai-generated-2023-04-24/. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Thaler, 130 F.4th at 1049-50 (discussing the Motion Picture Association’s Comment warning that technologies not previously seen as AI could shift to be included within the definition). ↑

- Copyright Review Board, Zarya of the Dawn (Registration # VAu001480196) (Correspondence ID 1-5GB561K), available at file:///Users/shelbyjorgensen/Desktop/CfAL/zarya-of-the-dawn.pdf ↑

- Midjourney, https://www.midjourney.com/home (last visited June 6, 2025). ↑

Disclaimer: This article is for educational purposes only and is not meant to provide legal advice. Readers should not construe or rely on any comment or statement in this article as legal advice. For legal advice, readers should seek a consultation with an attorney.

You must be logged in to post a comment.