Case Review: Rock’n’Roll, Museums, and Copyright Law (2020)

March 19, 2021

By Laura Michiko Kaiser

Marano v. Metropolitan Museum of Art, No. 19-CV-8606, 2020 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 122515 (S.D.N.Y. July 13, 2020).

Art galleries, museums, and auction houses all produce online and print catalogs, along with other promotional materials, to commemorate their exhibitions. Images of copyrighted artworks included in these catalogs may be created by the artist, by the estate or trust controlling underlying copyrights, or by the museum or gallery itself.[1] What rules govern arts institutions’ ability to reproduce images of art on their websites and in print catalogs? With the rise of virtual viewing rooms and digitization of art collections, what laws should arts institutions consider when deciding to publish an art image online?

Last summer the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York (“SDNY”) reviewed and analyzed this exact issue when a photographer sued the Metropolitan Museum of Art (“Met”) for the Met’s display of one of his photographs on their website.[2] Despite the SDNY’s decision in favor of the Met,[3] the question of whether reproductions of copyright-protected works in exhibition catalogs are permissible remains unclear.

The Exclusive Rights and Fair Use

Copyright law in the United States protects original works of authorship as soon as they are “fixed in any tangible medium”; registration with the Copyright Office is not required for the work to gain protection.[4] Original copyright owners, including visual artists, have six exclusive rights to exploit their work economically.[5] The most pertinent rights reserved by Congress to the creators are the ability to copy and distribute copies of the work to the public and to display the work publicly.[6] However, a legal defense known as “fair use” might apply where non-copyright holders avail themselves of one of the exclusive rights without obtaining permission from the copyright holder.[7]

For example, imagine a museum prints an image of a painting in an exhibition catalog without the copyright holder’s permission. The copyright holder sues the museum, claiming the museum illegally infringed by copying and displaying the work publicly. To defend itself, the museum might counter claim that the image in the catalog is “fair use” of the painting. If a court agrees with the museum, the museum would not pay any damages for copyright infringement. To decide if an image reproduction is “fair use” a court will use a four-factor test: i) what is the purpose and character of the use; ii) what is the nature of the original work; iii) what amount of the work was used in proportion to the original work as a whole; and iv) what is the effect of the non-copyright holder’s use on the potential market for the original work.[8]

Addressing this four-factor test, the Supreme Court has emphasized the “transformative” and commercial nature of the use: the more “transformative” the use is, the more likely it is fair use— and the more commercial the use is, the less likely it is fair use.[9] “Transformative” in this context means how much the potential infringer has changed the original “expression, meaning, or message” of the work.[10] Because the analysis is fact-dependent, avoiding copyright infringement is not always clear for the art institution seeking to publish the image.

Marano v. Metropolitan Museum of Art

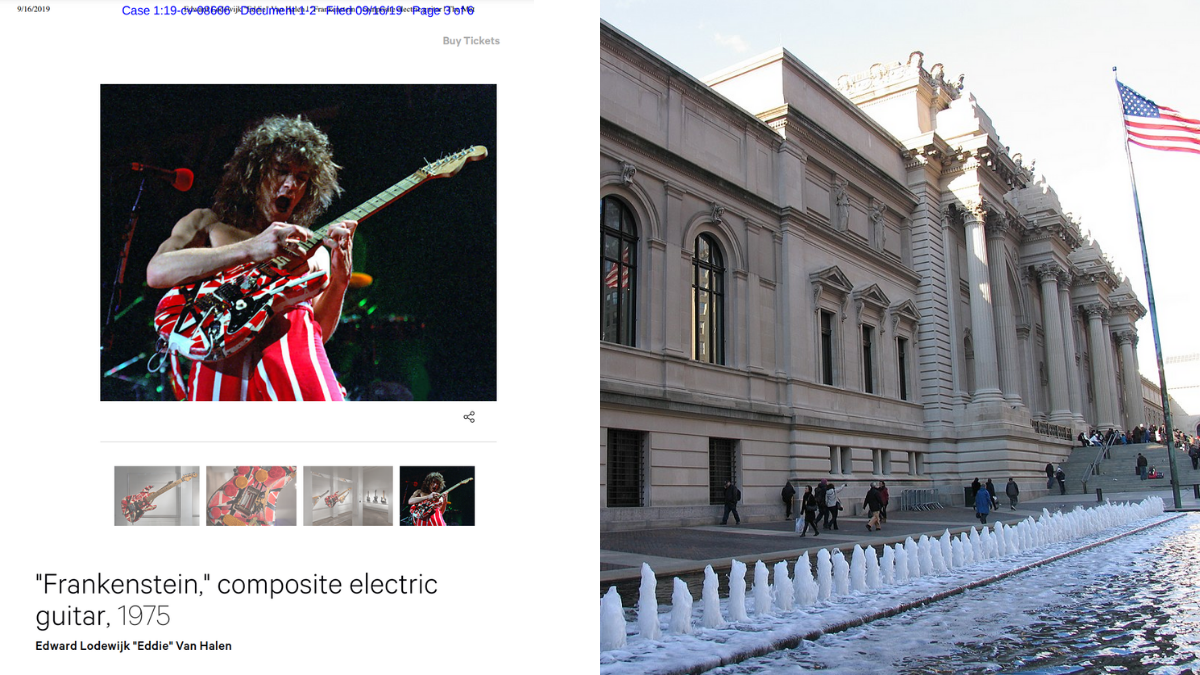

In Marano v. Metropolitan Museum of Art, the court analyzed the Met’s unauthorized use of an image on its website in connection with an exhibition called “Play it Loud: Instruments of Rock & Roll.”[11] The Met exhibit included the famous “Frankenstein” guitar, and the image in question was a photograph (taken by the plaintiff Lawrence Marano) of Eddie Van Halen playing the “Frankenstein” guitar at a concert.[12] Ultimately, the court dismissed the lawsuit ruling that the Met’s display of the photo was fair use.[13] The court’s rationale suggests how this issue may be resolved in the future.

The court methodically considered the four-factor fair use test and applied it to the circumstances, emphasizing that publication on the Met’s website changed the photo’s original purpose and character.[14] The court’s opinion divided the first factor, “purpose and character of the use,” into two sections: transformative use and commercial nature.[15] The Court found that: (1) the Met presented Marano’s photo of the “Frankenstein” guitar in a recognizable historical context; (2) the Met displayed the photo in a scholarly context; and (3) the photo was a minimal part of the Met’s online catalog.[16] The court resolved without much discussion that the photo’s reproduction was commercial—despite the Met’s status as a nonprofit organization—because the museum charges general admission fees to out-of-town visitors.[17]

The other three factors—ii) the nature of the work, iii) the amount and substantiality of the portion used, and iv) the effect on the market for the original—are discussed more briefly. The fact that the photograph is a creative, published work favors the artist’s claim for infringement.[18] The court favored the Met for the third factor (the amount used) because the museum reduced the image’s size and interspersed text and other photographs (even though the entire image was displayed).[19] The court also found it unlikely that the Met’s display of the photo on their website would affect the market for the original photograph.[20] Based on the court’s analysis, the Met did not infringe because the photograph’s original purpose was “transformed’ by its presentation on the museum’s website.[21]

Of course, the creation of digital collections and the publication of art images online is not only done in the U.S. A brief comparison of the U.S. and European copyright regimes and a closer look at a very helpful World Intellectual Property Organization (“WIPO”) report reveal the common confusion surrounding this copyright issue in museums worldwide.

Comparing the U.S. and European Copyright Regimes

European copyright law generally features stronger protections for artists than U.S. law and emphasizes protection for the creator.[22] U.S. law focuses on the value of the art and the financial consequences of copyright law.[23] Because of this difference in priorities, there are much more narrow and limited circumstances when unauthorized uses of artwork are permitted in Europe.[24] The U.S. copyright structure provides more room for excused unauthorized reproductions, mostly through the fair use defense.[25] Given this distinction, European courts would likely rule against galleries and auction houses in disputes that arise over unauthorized displays of art images.[26]

According to the World Intellectual Property Organization’s Revised Report on Copyright Practices and Challenges of Museums published in 2019 (“the WIPO Report” or “the Report”),[27] museums in most regions, including Europe, usually request permission from the copyright owner before using copyrighted works in promotional or marketing materials, though the Report notes that this area requires further exploration.[28] The Report concludes that there is a lack of awareness in the museum community around copyright law, the exceptions for unauthorized uses, and license practices generally.[29]

Takeaways

Turning back to U.S. practice, the Marano cases’ impact on the broader art community remains to be seen. One key question going forward is whether other organizations in similar circumstances will alter their approach to reflect the SDNY’s ruling. Because “fair use” requires a balancing of the four factors in the context of each case, it is difficult to predict how a given scenario might be treated by the court.

There is also a clear distinction between for-profit and nonprofit organizations: galleries and auction houses would likely need to be more cautious than non-profit museums in using unlicensed images. Galleries and auction houses may sell their catalogs, making these uses more obvious commercial ventures. The goals of galleries and auctions are also to sell the artwork itself, unlike a museum’s objective to display the work publicly.[30] Museums’ copy and display of art images is also more likely to be transformative than in auction catalogs because museums can argue scholarly and educational purposes.[31] Without some explicit exception in copyright law, it is unlikely that a gallery would knowingly reproduce images of art without license or permission.

Typically, artists readily give permission to the organization because the promotional materials bring the artists publicity and recognition.[32] However, when some dispute or negotiation is involved, the conservative approach of these institutions is to obtain a license or refrain from using the image.[33] Arts organizations generally prefer to maintain good relationships with artists and avoid risking a dispute.[34] The result in Marano is probably not enough on its own to change the current licensing arrangements between museums and artists regarding rights to copy and display images of copyrighted works.

U.S. museums, galleries, and auction houses are subject to a relatively unpredictable test before the court in cases that concern using unlicensed images of art in print and online materials. Arts institutions will likely continue to take a conservative approach and seek approval from the copyright holder before using an image of copyrighted art, despite recent case law finding fair use in similar circumstances.[35]

UPDATE AS OF 04/02/2021: The Second Circuit affirmed the SDNY’s decision and held that the Met’s display of Marano’s photo was fair use. Emphasizing transformative use (as the SDNY did), the Second Circuit found that Marano’s purpose in creating the photo was to show Van Halen performing, whereas the Met displayed the photo to highlight the Frankenstein guitar design and its position in rock and roll instrument history. The court quickly resolved the rest of the fair use analysis stating that the transformative use of the image colors the remaining three factors. In a subtle divergence from the SDNY, the Court of Appeals noted that this was not commercial use because the subject of Marano’s claim was the Met’s website, which is free and viewable by the general public. The Second Circuit also rejected Marano’s argument that finding fair use here will allow museums to claim scholarly and educational purposes for all copyrighted photos they use. The court reiterated that the fair use analysis is deeply dependent on case context and facts. Marano v. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, No. 20-3104 (2d Cir. April 2, 2021).

Endnotes:

- Barry Werbin, Use of Art Images in Gallery and Auction Catalogues: Copyright Minefield and Practical Advice, Herrick Feinstein LLP, Art & Advocacy, Vol. 10 (Oct. 2011). ↑

- See Marano v. Metropolitan Museum of Art, No. 19-CV-8606, 2020 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 122515 (S.D.N.Y. July 13, 2020). ↑

- See Marano, 2020 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 122515, at *19. ↑

- 17 U.S.C. § 102(a); 17 U.S.C. § 408(a). ↑

- 17 U.S.C. § 201(a); 17 U.S.C. § 106; but cf., 17 U.S.C. § 201(b) (in the work made for hire context, the person or employer who the work was prepared for owns the copyright in the work). ↑

- 17 U.S.C. § 106(1, 3, 5). ↑

- 17 U.S.C. § 107; Also, using copies of copyrighted works for “criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching…scholarship, or research” does not infringe. 17 U.S.C. § 107. ↑

- 17 U.S.C. § 107(1-4); See Sony Corp. of America v. Universal City Studios, Inc., 464 U.S. 417 (1984); Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc. v. Nation Enterprises, 471 U.S. 539 (1985); Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., 510 U.S. 569 (1994). ↑

- See Campbell, 510 U.S. at 579; Sony Corp. of America, 464 U.S. at 448-450. ↑

- Campbell, 510 U.S. at 579. ↑

- Marano v. Metropolitan Museum of Art, No. 19-CV-8606, 2020 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 122515 (S.D.N.Y. July 13, 2020). ↑

- Marano, 2020 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 122515, at *1-2. ↑

- Id. at *19. ↑

- Id. at *7-14, *19. ↑

- Id. at *7-14. ↑

- Id. at *7-12. This transformative analysis references language in Section 107, which provides that fair use includes uses “such as…scholarship.” 17 U.S.C. § 107; The court also relied substantially on a prior case concerning a book containing unlicensed images of Grateful Dead concert posters. See Bill Graham Archives v. Dorling Kindersley Ltd., 448 F.3d 605, 607-608 (2d Cir. 2006) (holding that including the poster images for a historical purpose—showing a biographical timeline of the band—was fair use). ↑

- Marano, 2020 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 122515, at *12-14. ↑

- Id. at *14. ↑

- Id. at *16. ↑

- Id. at *18. ↑

- See id. at *7-14, *19. ↑

- Florian Moritz & Dr. Daniela Mohr, What Are the Differences between European Copyright and U.S. Copyright?, Copytrack (Apr. 25, 2019) ↑

- See Moritz & Mohr, supra note 27; but see, 17 USC § 106A (codifying the Visual Artists Rights Act of 1990 and provisioning for moral rights of artists). ↑

- See Moritz & Mohr, supra note 22. ↑

- Id. ↑

- Indeed, a French court has done so recently in the case of a photographer of furniture for auction house catalogs. See Hans Neuendorf, French Court Copyright Law Ruling Threatens Art Market Price Transparency, ArtNet News (Mar. 17, 2015). ↑

- World Intellectual Property Organization [WIPO], Standing Committee on Copyright and Related Rights, Revised Report on Copyright Practices and Challenges of Museums, at 24, SCCR/38/5 (Mar. 29, 2019). Through interviews with thirty seven museums worldwide, the WIPO Report explores copyright challenges museums face when acquiring, preserving, and exhibiting works and communicating the museums’ activities to the public, but does not identify the specific countries or museums interviewed. Id. at 4-7, 9. No equivalent report specifically addressing museums has been issued by the U.S. Copyright Office, but the Association of Art Museum Directors’ Guidelines for the Use of Copyright Material and Works of Art by Art Museums is an important resource for U.S. museum counsel. See See Association of Art Museum Directors, Guidelines for the Use of Copyrighted Material and Works of Art by Art Museums, at 13 (Oct. 11, 2017); but cf. U.S. Copyright Office, Section 108 of Title 17: A Discussion Document of the Register of Copyrights (Sept. 2017) (identifying issues with 17 U.S.C. § 108 and proposing revisions so that libraries and archives have a strong and balanced safe harbor in order to fulfill their missions). ↑

- World Intellectual Property Organization [WIPO], Standing Committee on Copyright and Related Rights, supra note 32, at 24, 39. There is an exception in Europe for digitization of orphan works for the purposes of cataloguing, preservation, and restoration. Id. at 19. ↑

- Id. at 4. ↑

- See Guidelines for the Use of Copyrighted Material and Works of Art by Art Museums, supra note 27. ↑

- See id. at 13 (explaining that just because the publication is sold does not automatically mean the use is commercial). ↑

- See Werbin, supra note 1. ↑

- See Werbin, supra note 1. ↑

- See Guidelines for the Use of Copyrighted Material and Works of Art by Art Museums, supra note 27, at 10. ↑

- See Marano, 2020 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 122515, at *19. ↑

About the Author:

Laura Michiko Kaiser is a third-year law student at The George Washington University Law School and legal intern at the Center for Art Law. Prior to law school, she worked as a paralegal in New York City. Laura earned her B.A. in Comparative Literature from New York University and completed course work in studio art, film, international literature, and cultural heritage. She is passionate about the art law field and hopes to be an attorney and advocate for artists and designers.

Disclaimer: This article is for educational purposes only and is not meant to provide legal advice. Readers should not construe or rely on any comment or statement in this article as legal advice. For legal advice, readers should seek a consultation with an attorney.